5 Surprising Truths About AI, Robotics, and the Future of Your Job

The Great Inversion: How AI & Robotics Are Rewriting Work, Wages, and Power

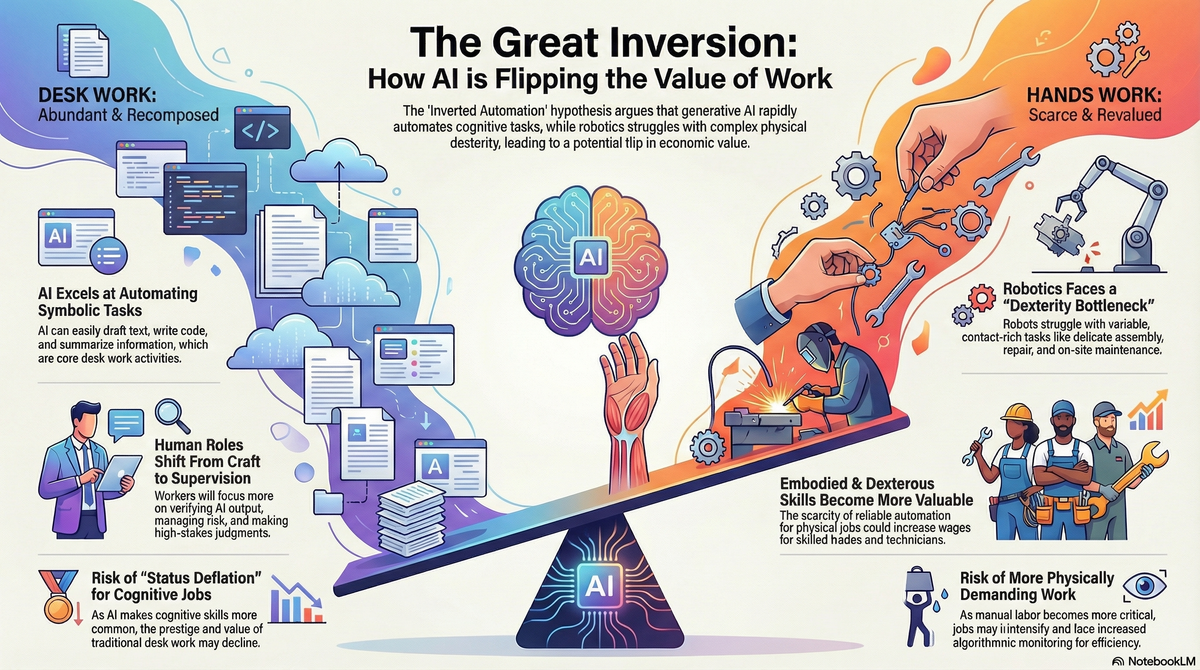

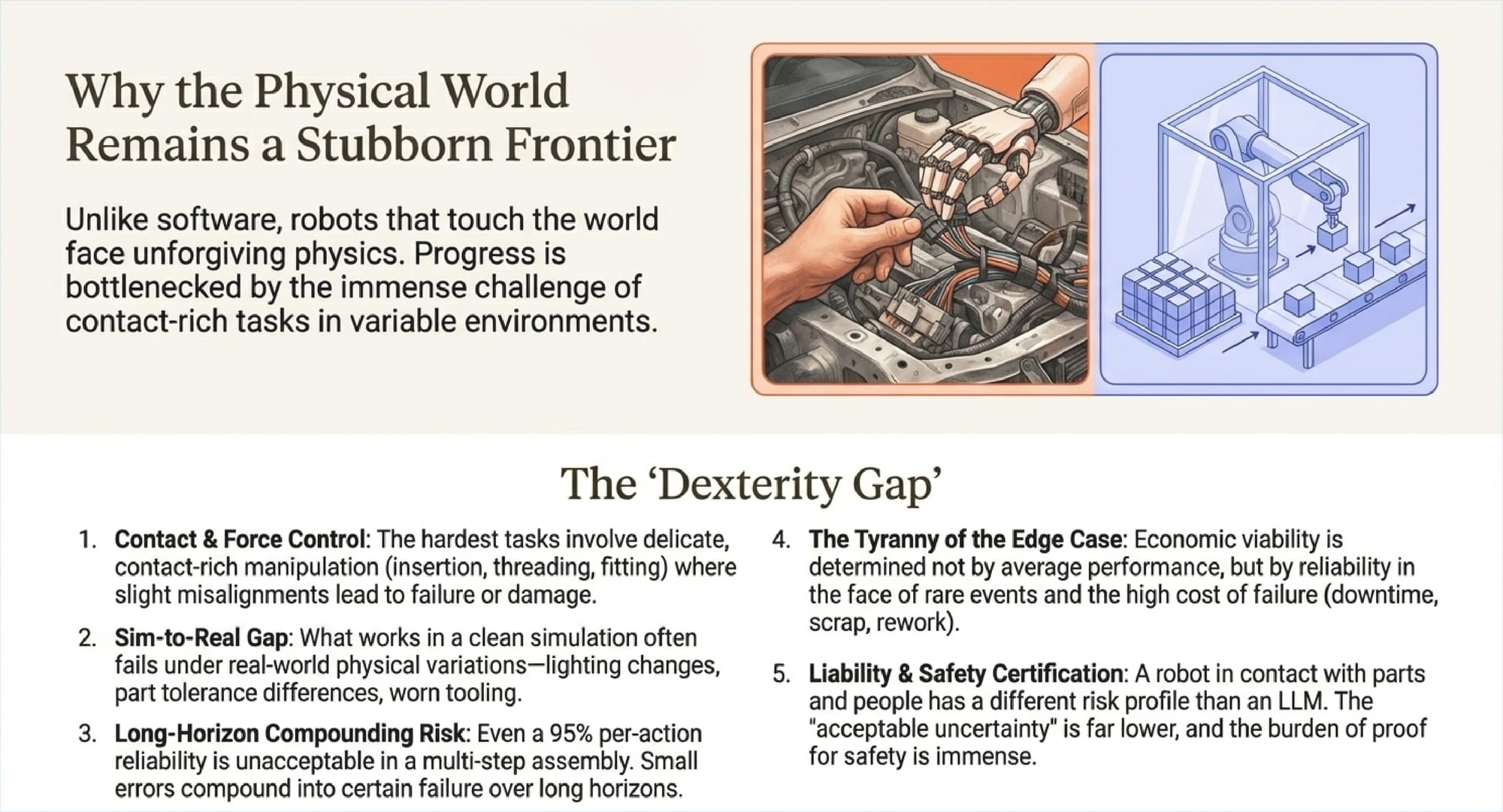

For years, the story about automation has been simple and consistent: robots will come for the routine, manual jobs first. Welders, assembly line workers, and truck drivers were on the front lines, while the complex, "thinking" jobs—the work of writers, programmers, and analysts—were considered safe for the foreseeable future.

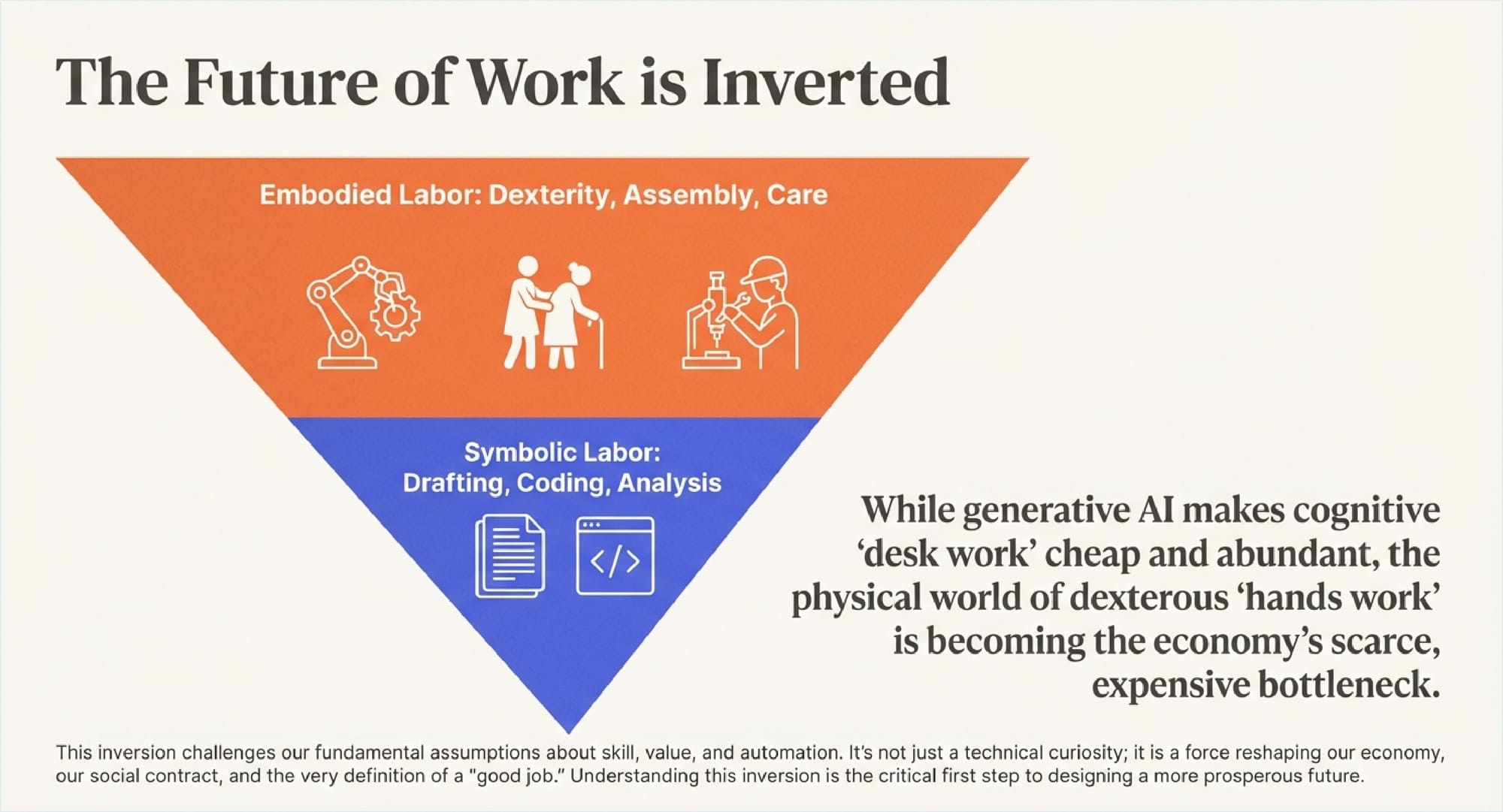

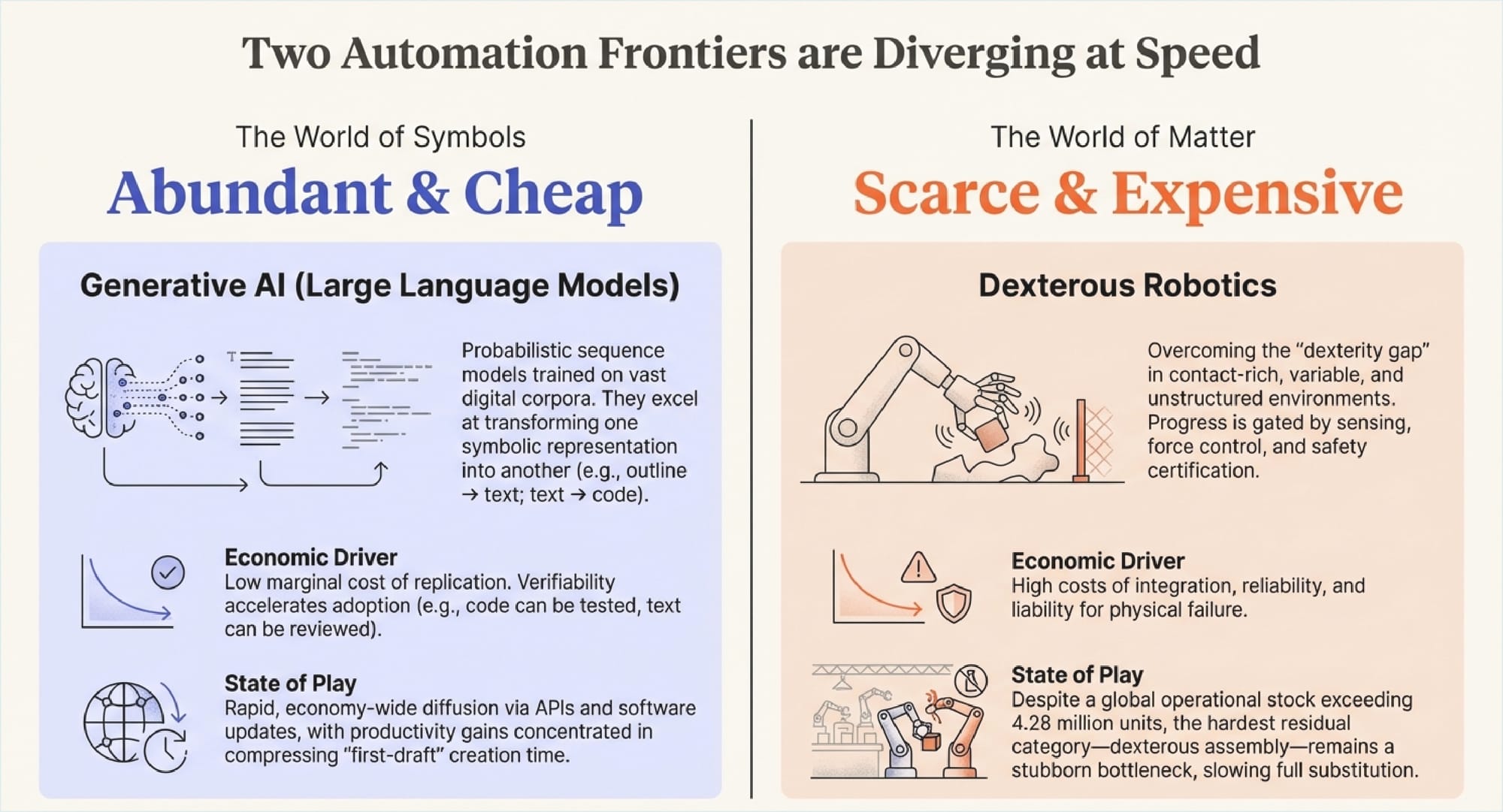

But what if that story is backward? A compelling new analysis suggests we're facing a period of "Inverted Automation," where the symbolic work done at a desk (e.g., drafting reports, writing code, summarizing regulations) may become cheap much faster than the dexterous work done by hand (e.g., aligning, inserting, fastening, and handling delicate parts). The digital nature of office work makes it a prime target for generative AI, while the physical world of atoms remains stubbornly difficult for robots to navigate.

Here are the five most surprising truths about this shift and what it means for the future of your job.

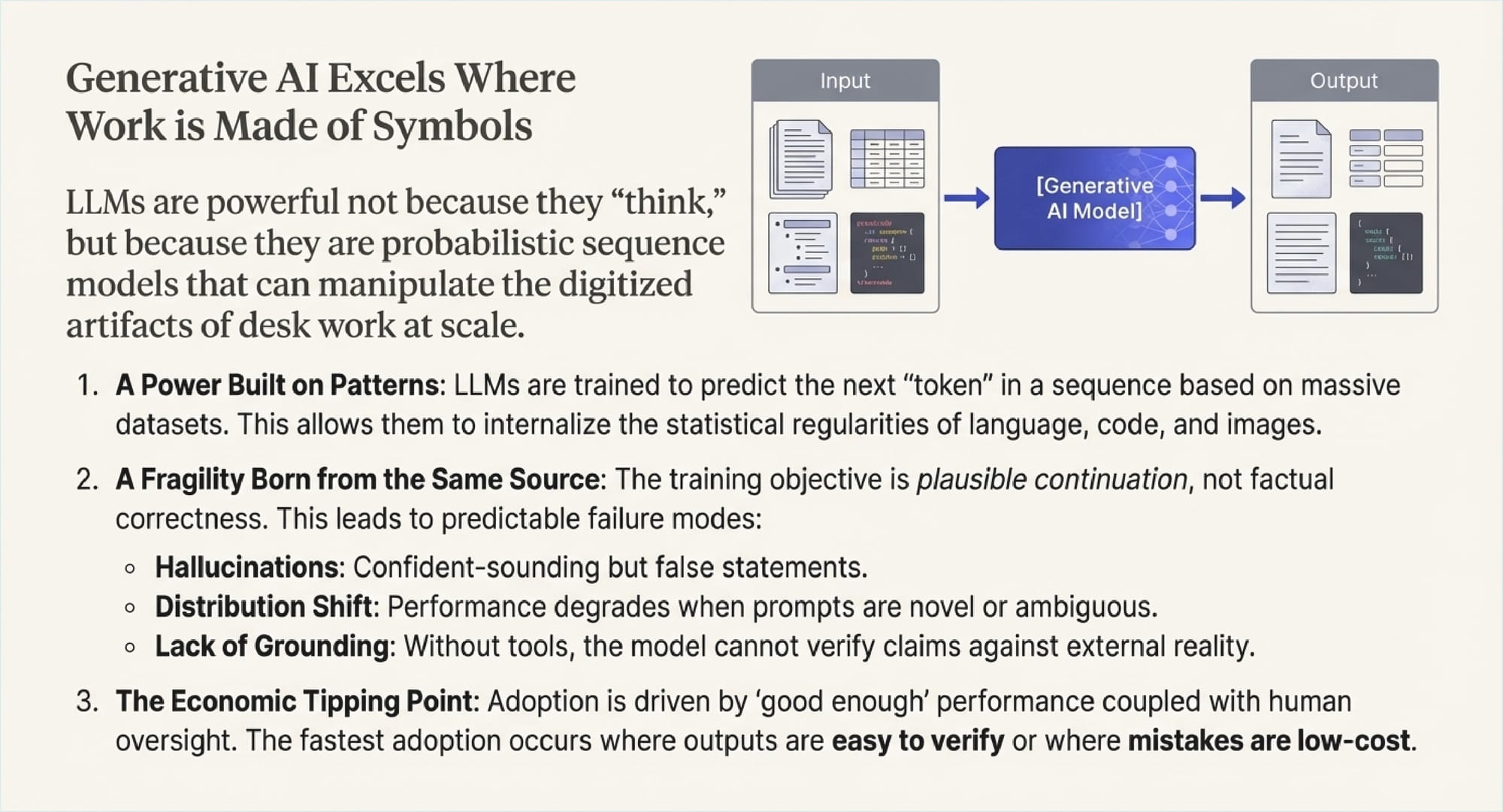

1. AI's First Target Might Be Your Desk Job, Not the Assembly Line

The core of the "Inverted Automation" thesis is that generative AI can perform or accelerate many symbolic tasks—the "Screen" work of writing, coding, and designing—with very little friction. Because this work is already digital, adopting AI tools is often as simple as opening a new browser tab.

Contrast this with robotics for "Hand" work. Deploying a robot in a factory is a complex, expensive project requiring physical integration, safety redesigns, and new workflows. In manufacturing, this is known as the "variability tax": every deviation from a perfectly structured environment—a slightly different part, a change in lighting, a minor misalignment—imposes costs through extra sensors, more complex software, and the high price of failure like scrap, equipment damage, and safety hazards.

This leads to a powerful new way to think about your own role:

1) Don’t ask “Will AI replace my job?” Ask: “Which parts of my work happen on a screen, which require hands, and which depend on unpredictable real-world situations?” Screen-heavy tasks tend to change fastest.

2) This shift from a job-centric to a task-centric view is critical, because it reveals where the new economic value is concentrating: not in generating drafts, but in owning the outcome.

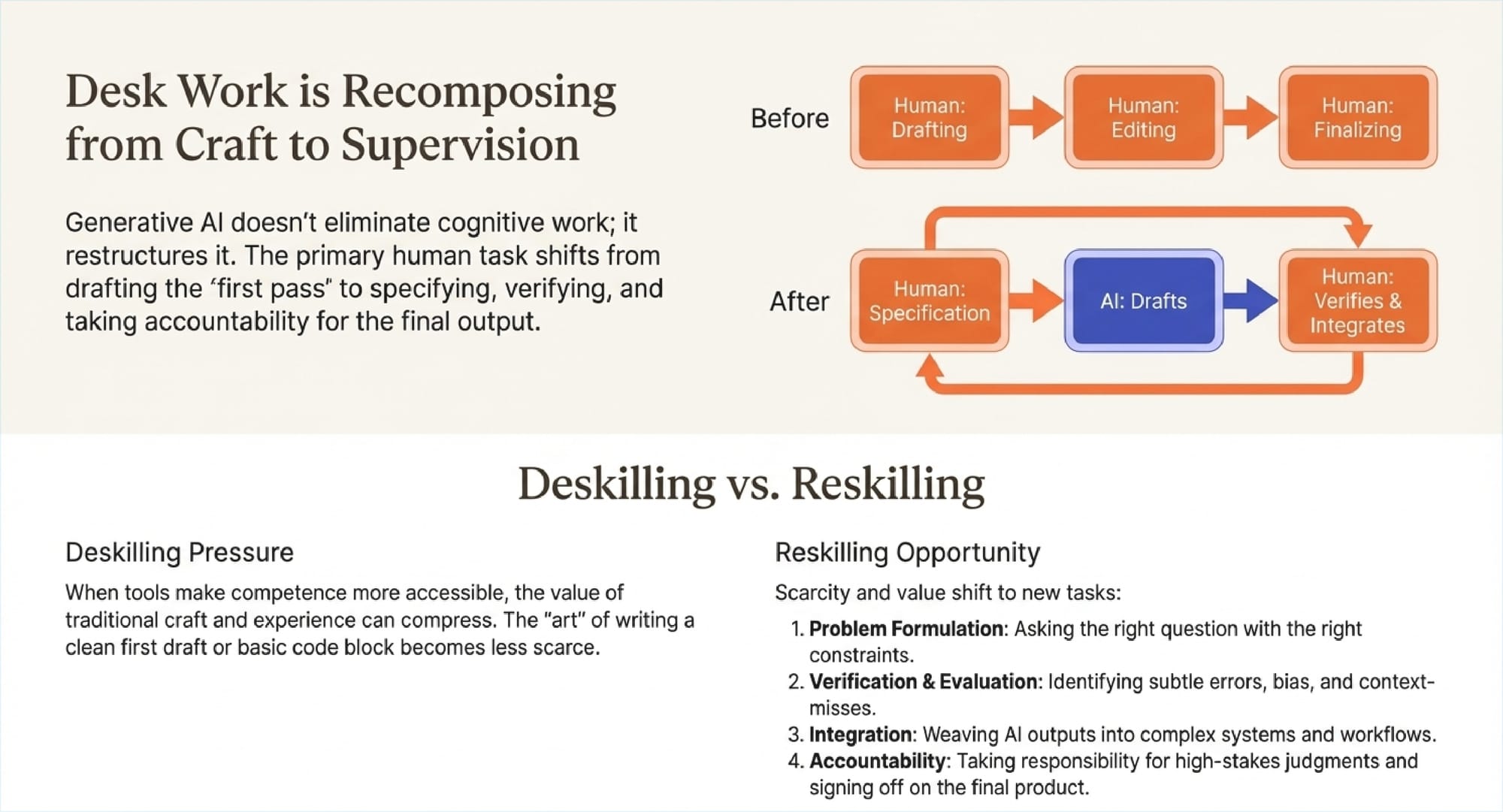

2. Technology Replaces Tasks, Not Jobs

One of the biggest errors in forecasting the future of work is focusing on job titles. A "job" is just a collection of many different activities, or "tasks." Technology rarely eliminates an entire occupation at once. Instead, it changes the mix of tasks within it.

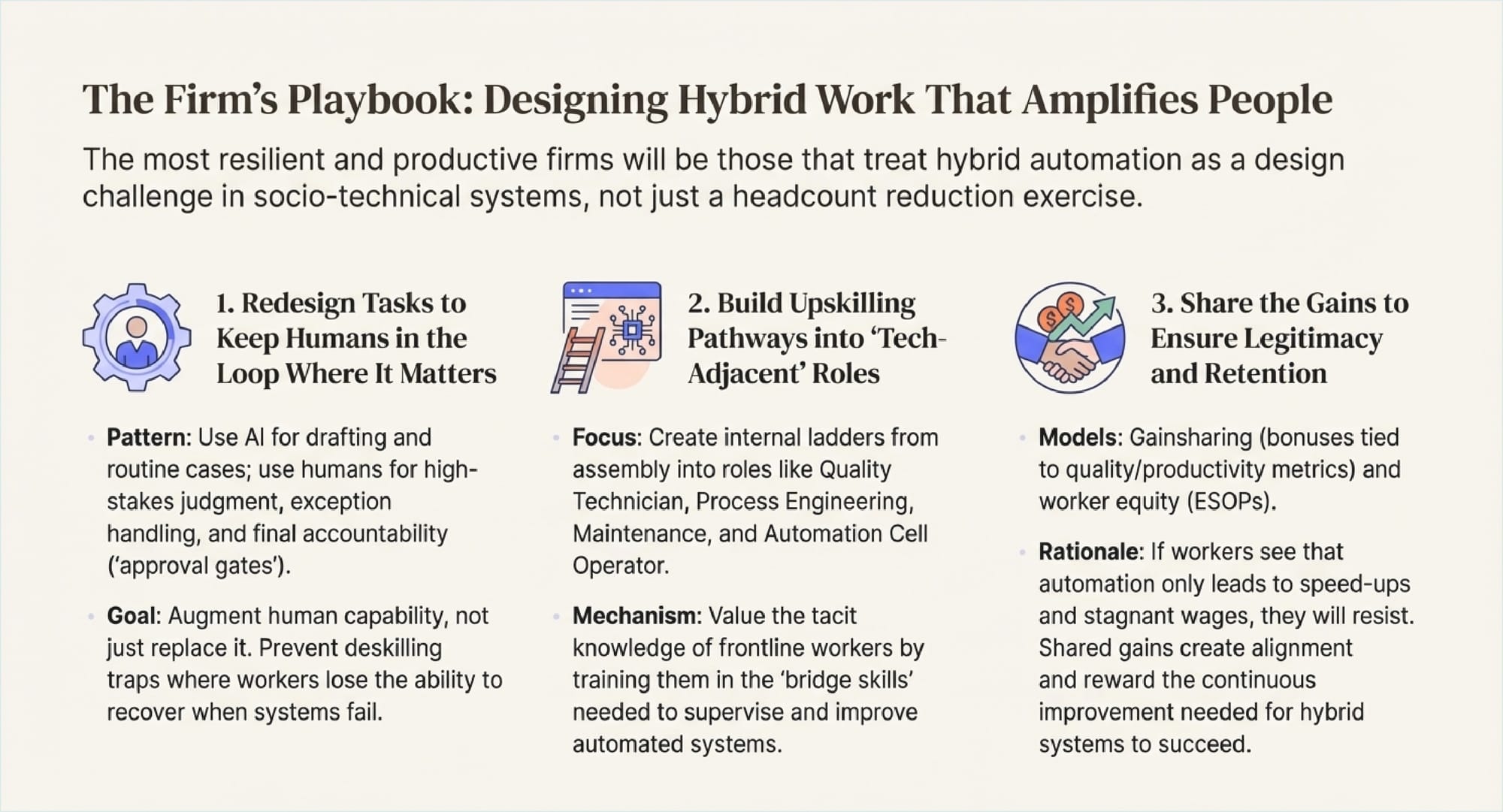

This process is called "task recomposition." AI might automate the task of writing a first draft of a report, but this creates new tasks like verifying the AI's output, integrating it with other information, and taking responsibility for the final product. The labor outcome depends on which tasks become the scarce, critical "O-ring" steps after the technology is adopted.

Forecasting based on job titles alone is often misleading because it misses this crucial nuance. The real question isn’t whether your job title will survive, but how the collection of tasks you perform every day will be reweighted, transformed, and redefined.

3. Your Real Value Isn't Drafting—It's Deciding

As generative AI makes "first drafts" of text, code, and designs nearly instantaneous and free, the economic bottleneck shifts. When one part of a process becomes cheap, the other parts often become more valuable.

The new premium skills are not about generation, but about judgment: verification, evaluation, integration, and, most importantly, accountability. Organizations need a human to be responsible for high-stakes outputs, because that person must be answerable to audits, courts, regulators, and internal quality systems. The technology can produce a draft, but a person must own the decision.

As drafting speeds up, checking and integration often become the new bottlenecks — and the new sources of value.

4. The Career "Ladder" for New Professionals Is Breaking

This reorganization of tasks—and the new premium on human judgment—has a direct and startling consequence for how professional careers begin. Many careers follow a predictable path where juniors start with foundational tasks like drafting memos, summarizing documents, or writing routine code. By doing this "draft work," they build the skills to take on more complex roles.

But if AI automates these entry-level tasks, the ladder breaks. Firms may shrink their junior cohorts because they no longer need a large pyramid of people to produce first drafts. This creates a "ladder problem" for new entrants, fundamentally changing how they learn and progress.

At the same time, it creates a "leverage problem" for seniors. A senior manager can now use AI to "multiply themselves," supervising far more output than before. This threatens to widen the gap between junior and senior roles, making it harder than ever to climb from one to the other.

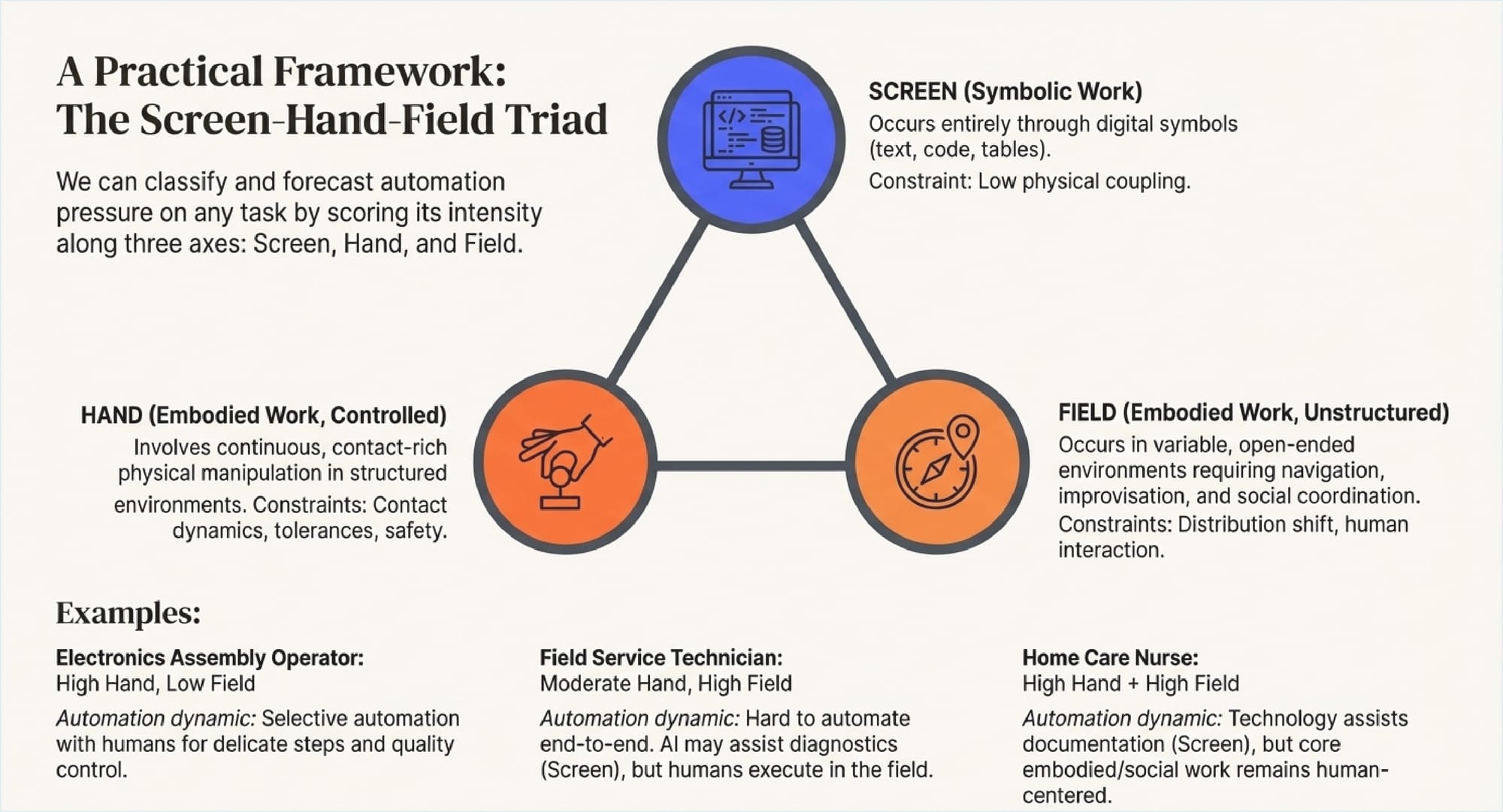

5. A Simple Framework to Analyze Any Job: "Screen, Hand, Field"

To understand how these forces might affect your own work, you don’t need a crystal ball—you just need a simple framework. Any job can be broken down into three types of tasks:

• Screen (Symbolic): Work whose inputs and outputs are digital symbols like text, code, documents, and spreadsheets (e.g., drafting reports, creating spreadsheets, writing code). This is where generative AI has the most immediate impact.

• Hand (Embodied): Work requiring physical manipulation and contact-rich interaction (e.g., assembly, soldering, installing fixtures, plumbing joints). This is much harder to automate due to the challenges of dexterity, sensing, and safety.

• Field (Situated): Work performed in unpredictable, open-world environments (e.g., maintenance on a construction site, repair in a messy warehouse, logistics in unpredictable spaces). This remains difficult due to environmental and social variability.

Putting the Framework to Use

You can apply this triad to your own job by asking a few simple questions for each task you perform:

• Screen Task Check: Is the work mostly documents and messages? Can its quality be evaluated through review? Is “good enough” acceptable, or must it be perfect?

• Hand Task Check: How variable are the parts? How much does success rely on the tacit “feel” of force and friction? What is the cost of a mistake?

• Field Task Check: Does the environment change often? Are there unpredictable exceptions? Are there safety constraints that demand human accountability?

The Real Question to Ask

The future of work is not a simple battle of humans versus machines. It’s a fundamental reorganization of tasks, skills, and economic value. The changes are happening faster in the digital world of screens than in the physical world of hands, upending our long-held assumptions about which jobs are "safe."

As one observer poignantly noted in a discussion on the topic:

People are extending LLMs a hand, hoping to pull them up to our level. But there's nothing reaching back.

Instead of asking, "Will an AI take my job?", the real question is how the system of work will be redesigned. Which tasks are becoming cheap, which are becoming priceless, and most importantly, what new workflows and responsibilities will emerge to connect them?