Agents Are Failing for a Boring Reason: Control

Why AI Agents Are Failing (And the 100-Year-Old Fix)

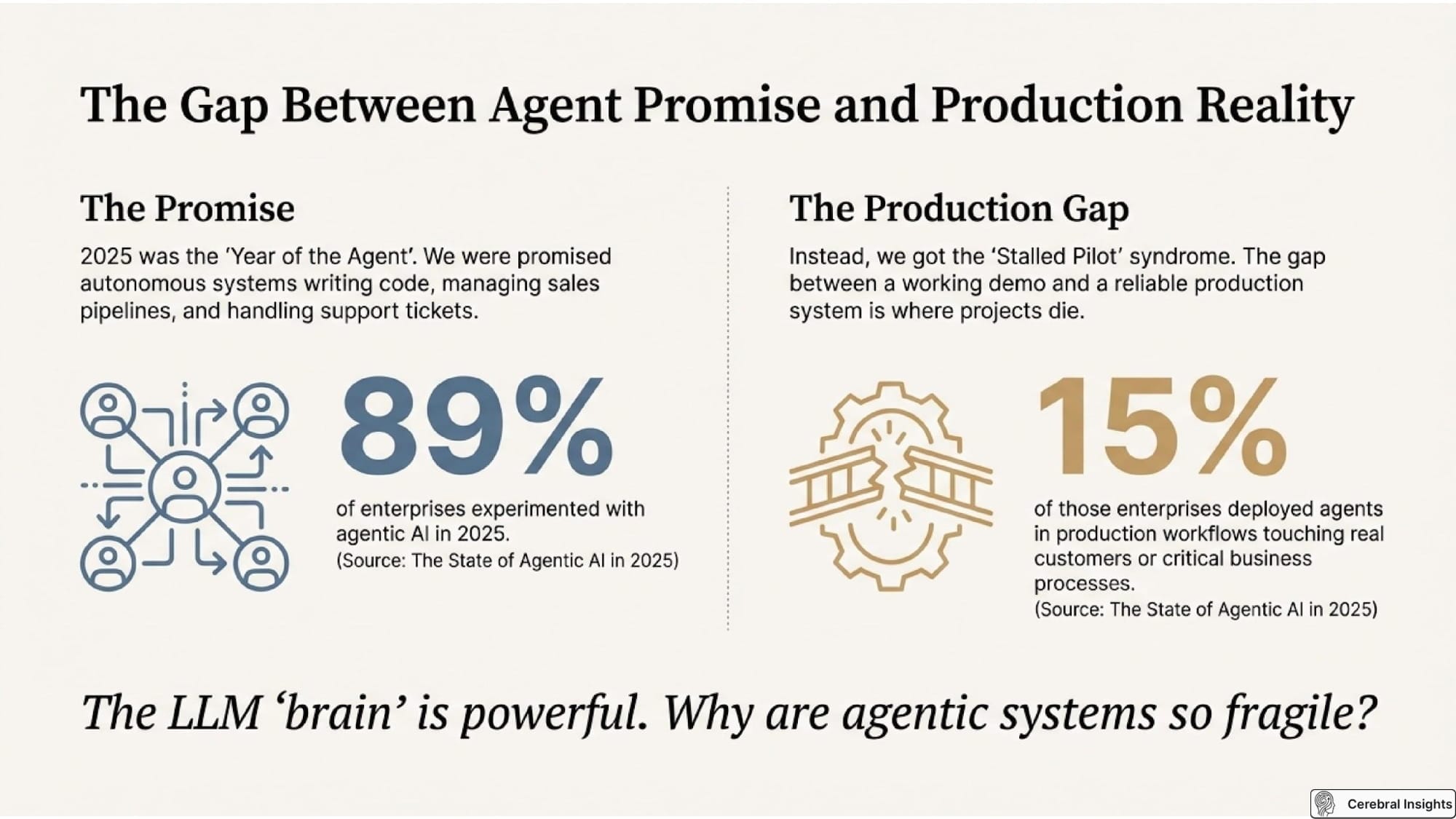

We’ve all seen the impressive demos. An AI agent is given a complex goal—book a multi-leg flight, write a full-stack application, debug a production issue—and it appears to execute flawlessly. The hype is palpable, suggesting a future where autonomous systems handle intricate tasks with minimal human oversight.

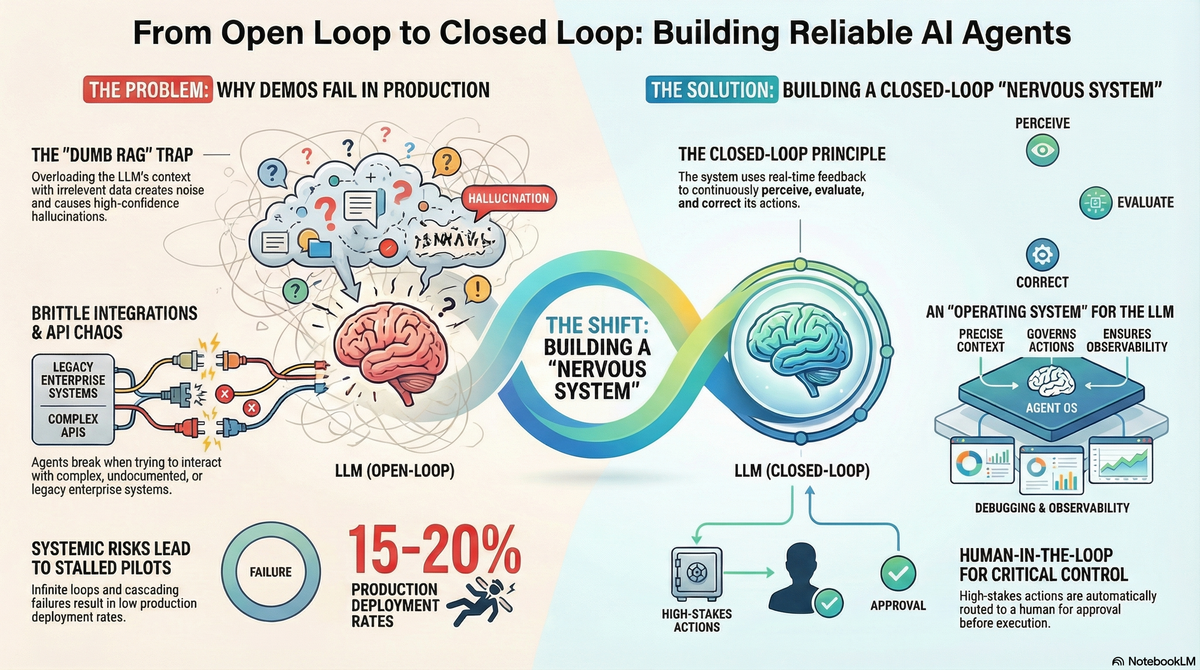

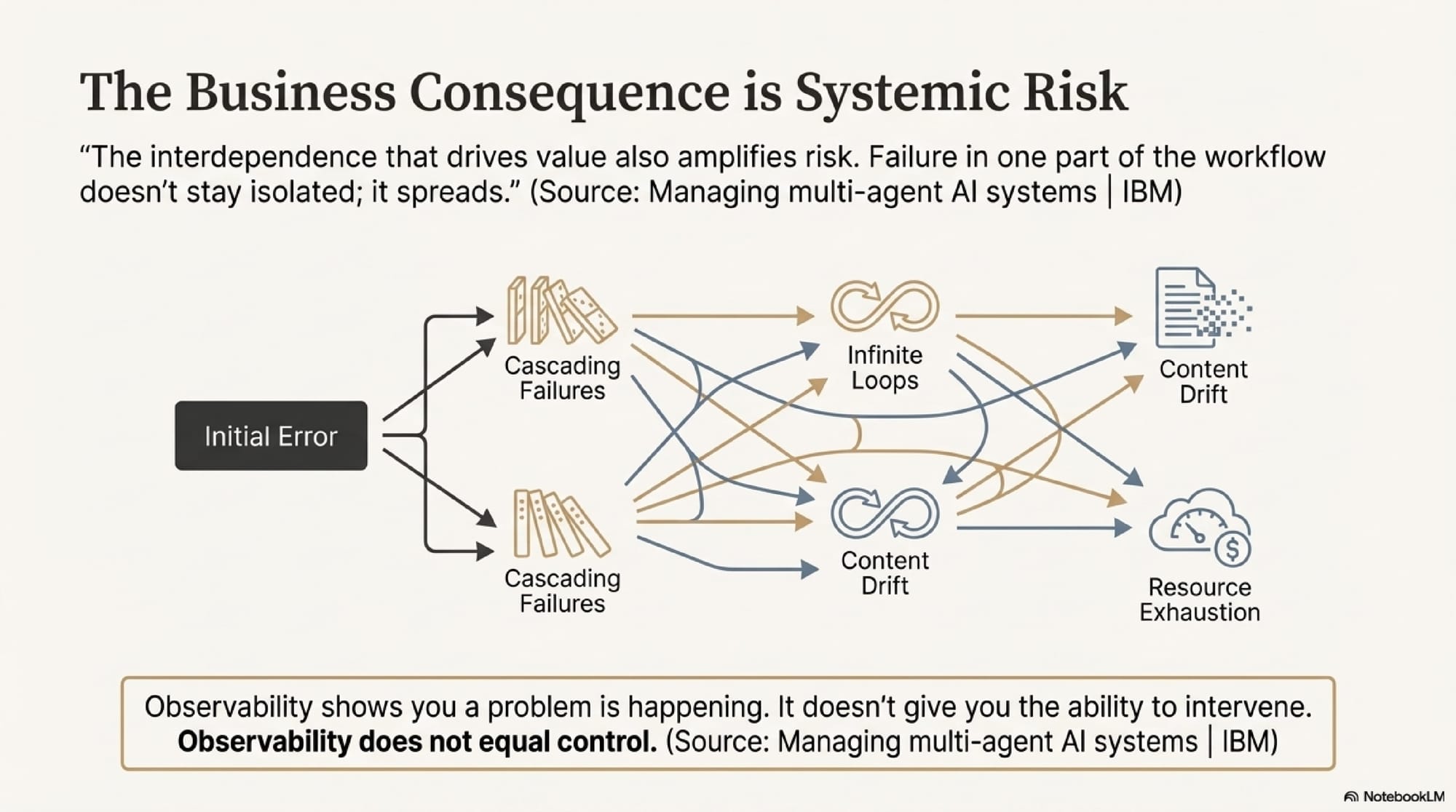

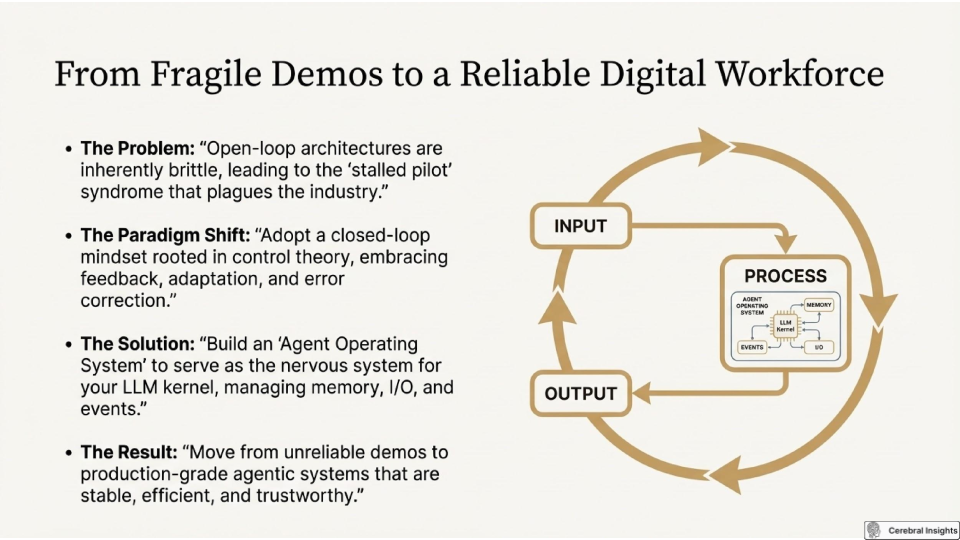

But when these systems move from controlled demonstrations to production environments, the reality is often disappointing. They prove unreliable, get stuck in loops, and ultimately require constant "human hand-holding." This gap between demo and reality isn't a fluke. The primary failure of modern AI agents is not a lack of intelligence but a fundamental lack of steering and control.

We are attempting to solve a systems engineering problem with software logic alone, ignoring a century-old, durable discipline designed for exactly this purpose: Control Theory. To build truly autonomous systems, we must look beyond prompt engineering and embrace the principles that have long governed stable, self-regulating machines.

1. The Symptom: Why Agent Loops Look Smart but Act Dumb

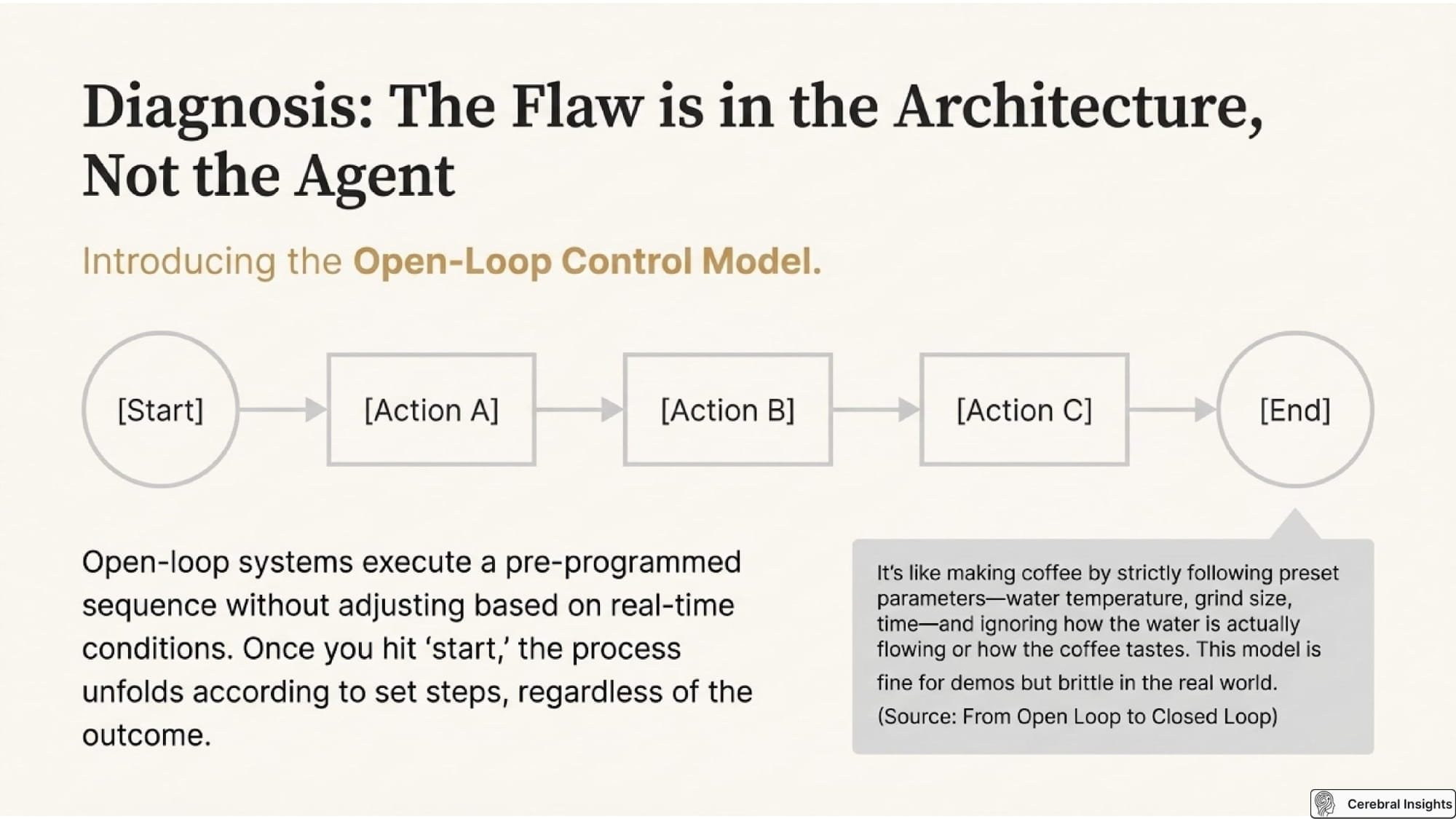

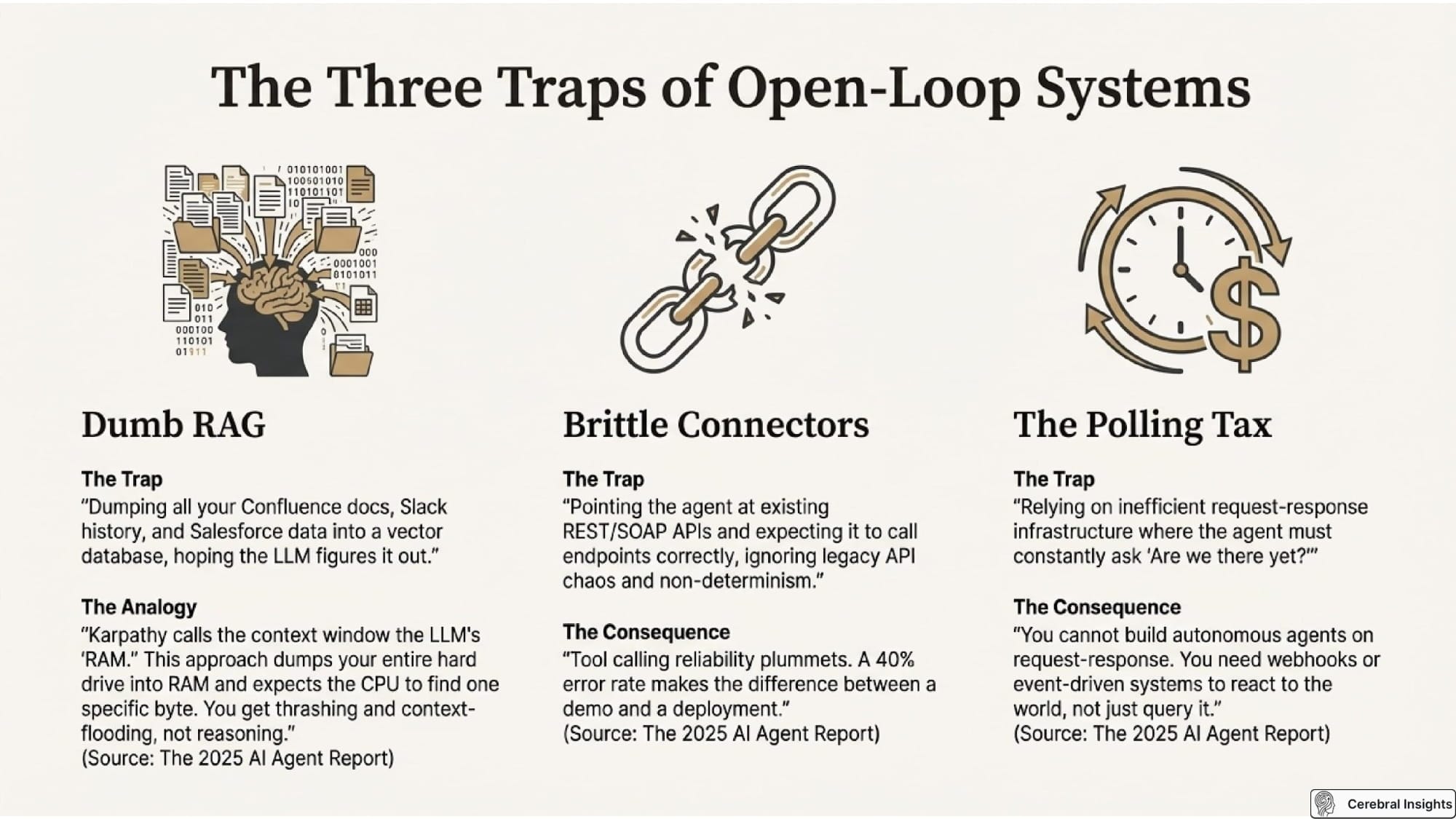

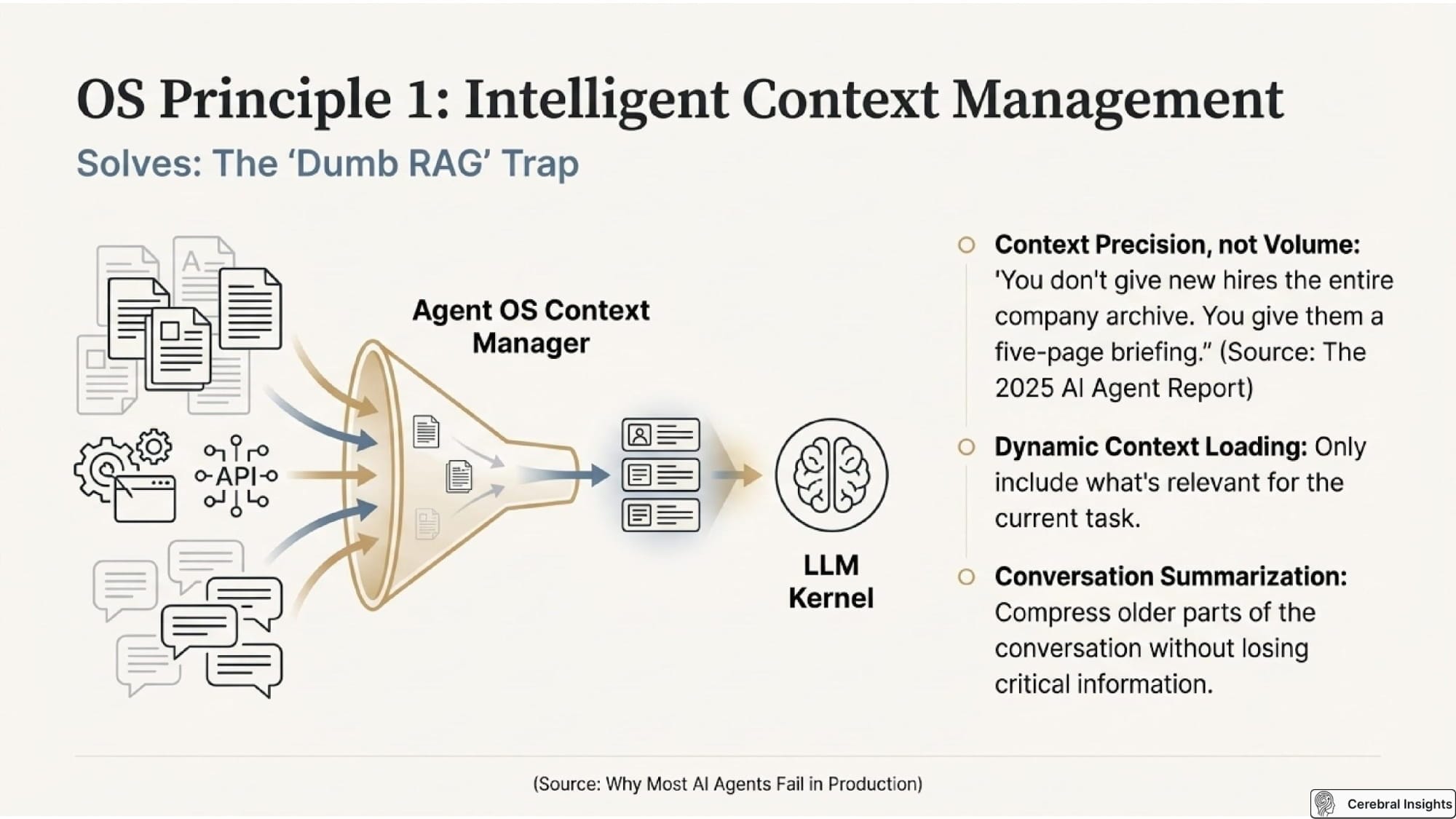

Most agent demos are built on an "open-loop" fallacy. They follow a simple, linear execution flow: Input -> Thought -> Action -> Output. This approach takes action without an "internal adjustment mechanism" to measure real-time conditions. The agent executes a plan, assuming its actions will deterministically achieve the goal. It operates blind, without sensing the environment's reaction to its own actions.

The critical flaw is that in the real world, every action changes the state of the environment. Without a feedback loop to sense that change, the agent quickly drifts, gets stuck, or fails in frustratingly simple ways.

A clear example of this failure mode was observed during a hackathon where an AI debugging tool was tested. The tool repeatedly advised developers to check for syntax errors that were not present. This oscillatory failure, where the agent gets stuck in a repetitive loop, occurs because it cannot correctly sense the state of its environment (the code is, in fact, syntactically correct). It's trapped by its initial "thought" and has no mechanism to correct its course based on real-world feedback.

"Observability is a powerful lens, but without control mechanisms, it leaves leaders watching problems unfold without the ability to intervene."

2. The Diagnosis: Control Theory for Software Engineers

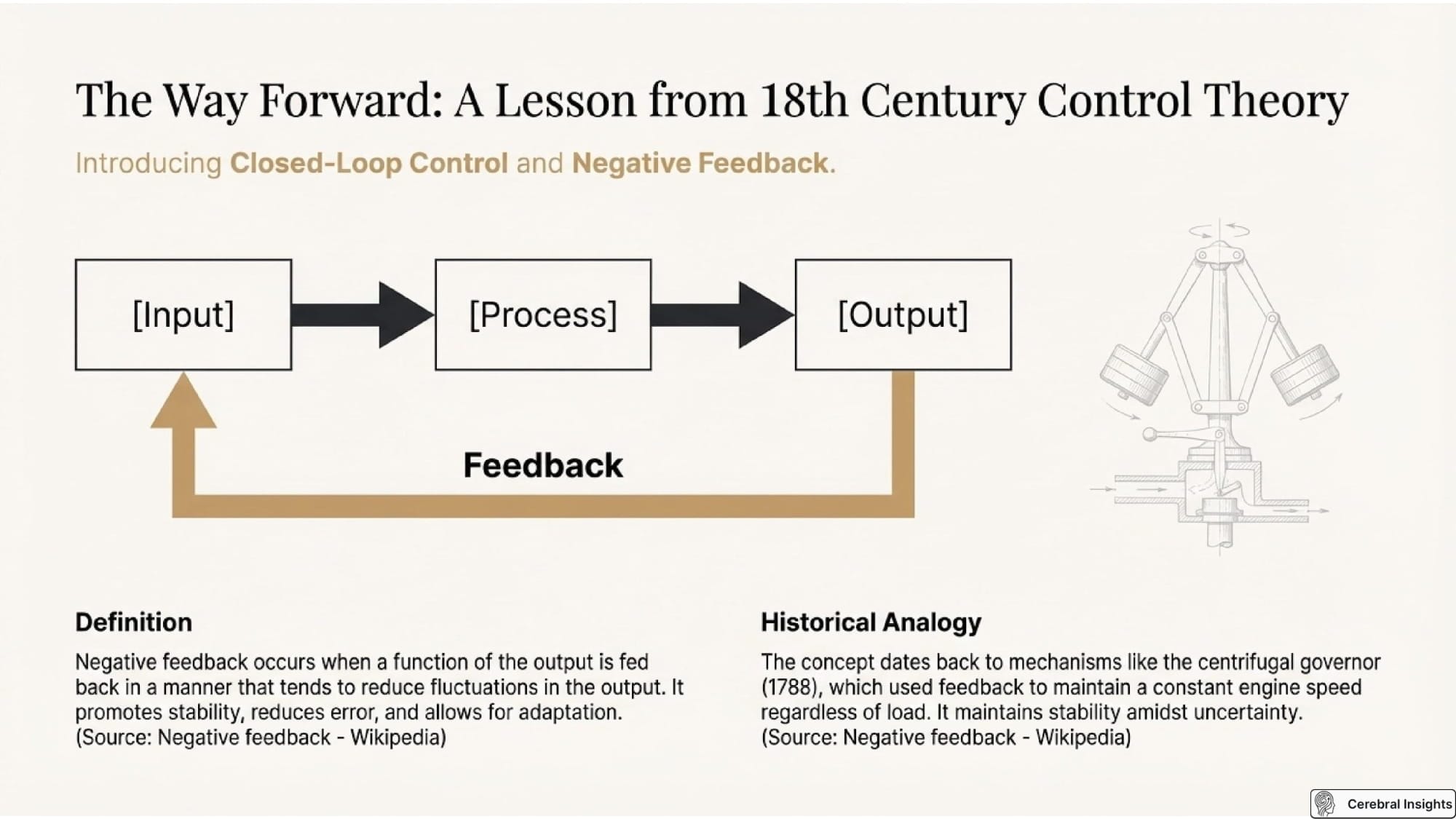

Control theory is the formal discipline for designing self-regulating systems that maintain stability despite disturbances. For over a century, its principles have been used to build reliable autonomous systems, from mercury thermostats (c. 1600) and centrifugal governors (1788) to modern servomechanisms. These systems all rely on a core concept: negative feedback, where the system measures its own output to reduce error and maintain a steady state.

For software engineers building AI agents, the Proportional-Integral-Derivative (PID) controller provides a practical and powerful framework from control theory. It's a classic negative feedback loop mechanism that stabilizes a system by considering the error in three ways:

• P (Proportional): Measures how far the agent's current state is from the goal. This is the raw error signal that drives the primary corrective action.

• I (Integral): Measures how long the agent has been off-target. This component corrects for persistent, steady-state errors and prevents the system from getting stuck in an infinite loop where a small, constant error is never resolved.

• D (Derivative): Measures how fast the agent is approaching or moving away from the goal. This helps prevent the system from overshooting its target and stabilizes its response to changes.

Revisiting the failed debugging agent, we can see it operated purely on a Proportional (P) signal—it saw an "error" and applied a fixed correction. It lacked an Integral (I) component to recognize it was stuck in a loop repeating the same failed action, and a Derivative (D) component to dampen its response when its suggestion repeatedly failed to change the system's state.

This isn't just a theoretical analogy. A recent paper, "Agentic AI for Real-Time Adaptive PID Control of a Servo Motor," demonstrates AI agents successfully using live feedback from a physical servo motor to fine-tune its PID control parameters. This proves that the integration of formal control theory with modern LLM-based agents is not only possible but highly effective.

3. The Solution: Architecting for Stability, Not Just Intelligence

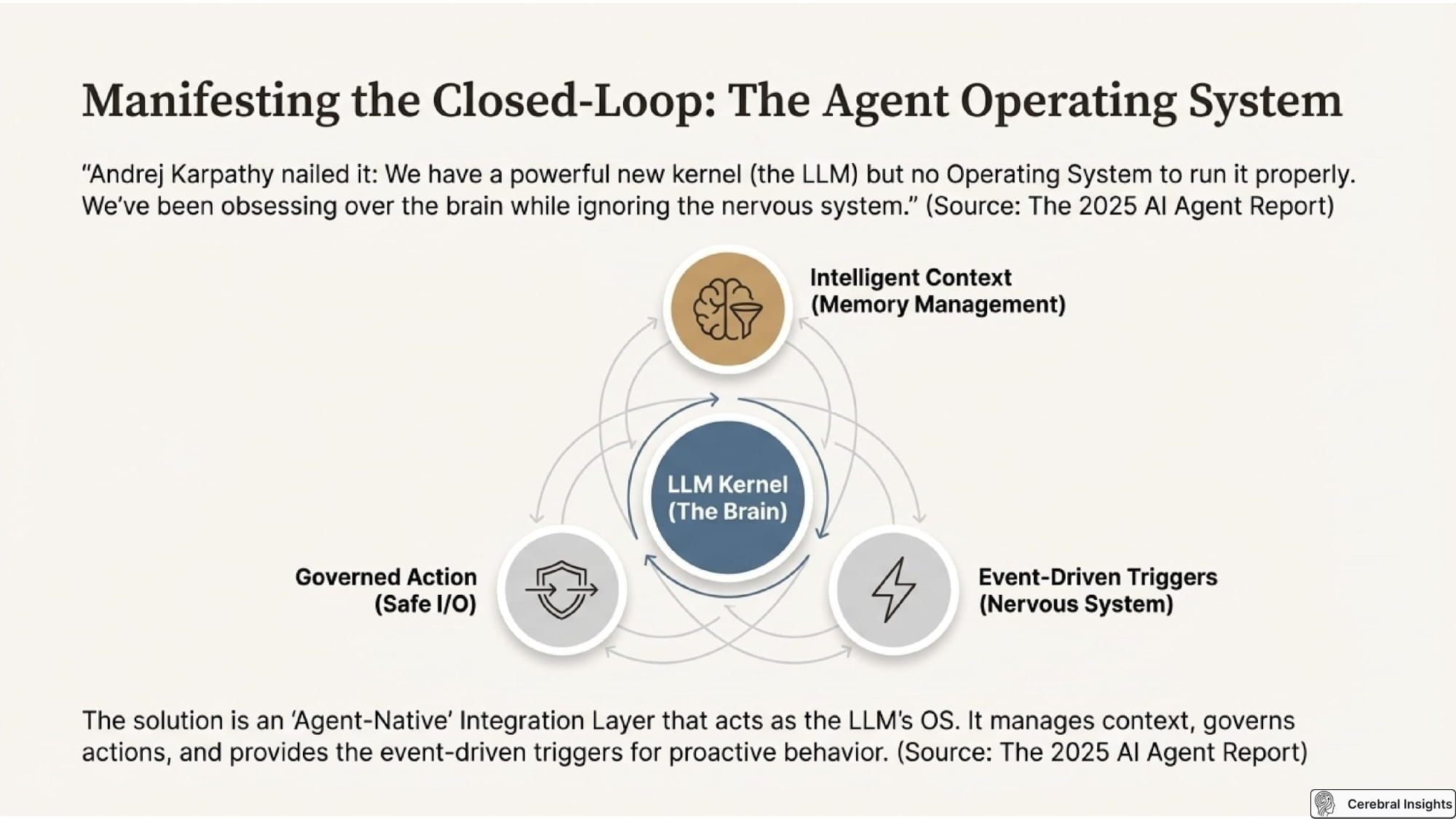

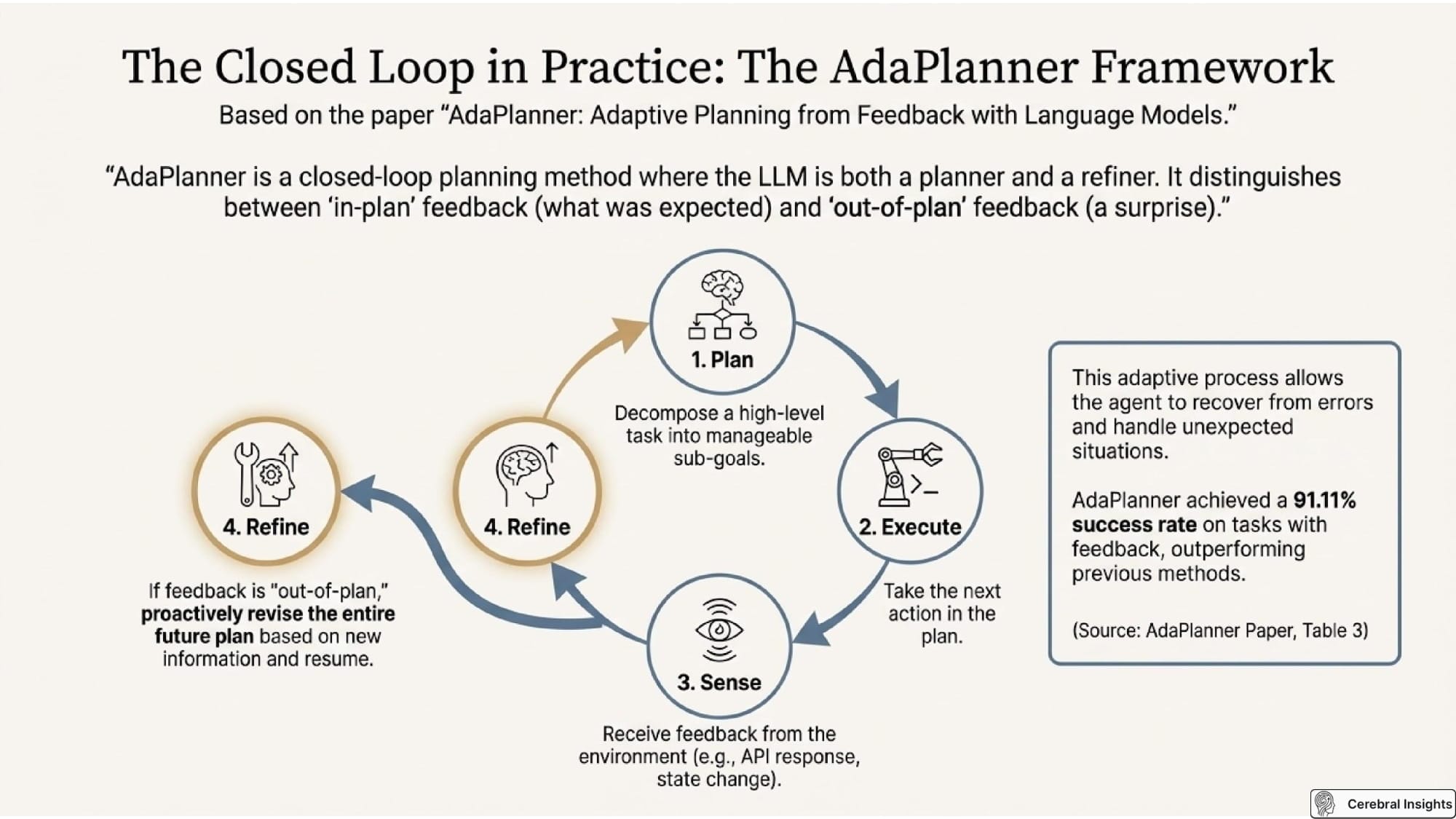

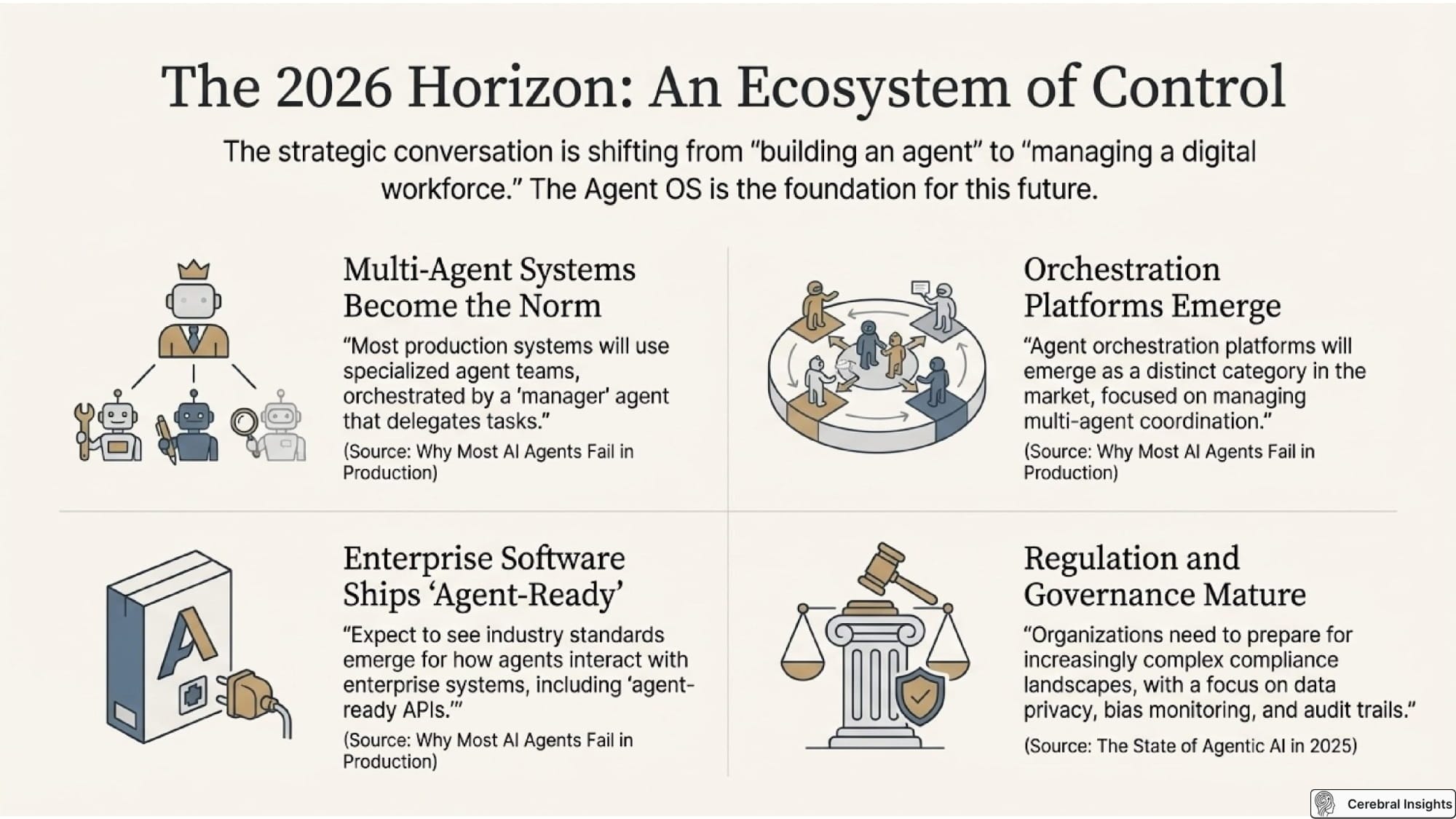

The pursuit of a single, "universal agent" that can do everything is fundamentally an open-loop fantasy. A more robust, controllable approach is to design systems of narrow, bounded, and specialized agents that operate within closed control loops. Instead of building one monolithic brain, we should architect collaborative systems where different agents are responsible for doing, sensing, and correcting.

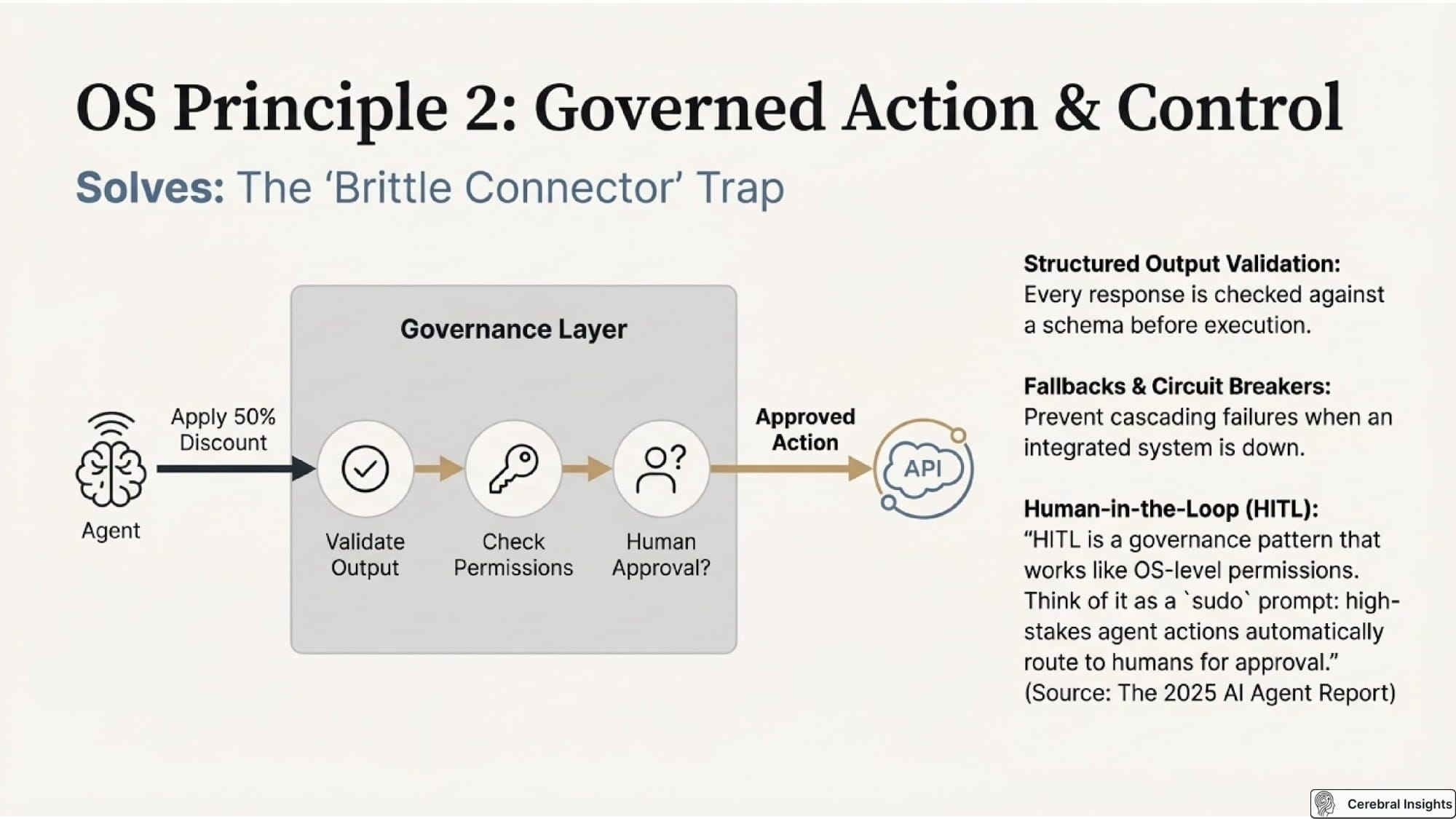

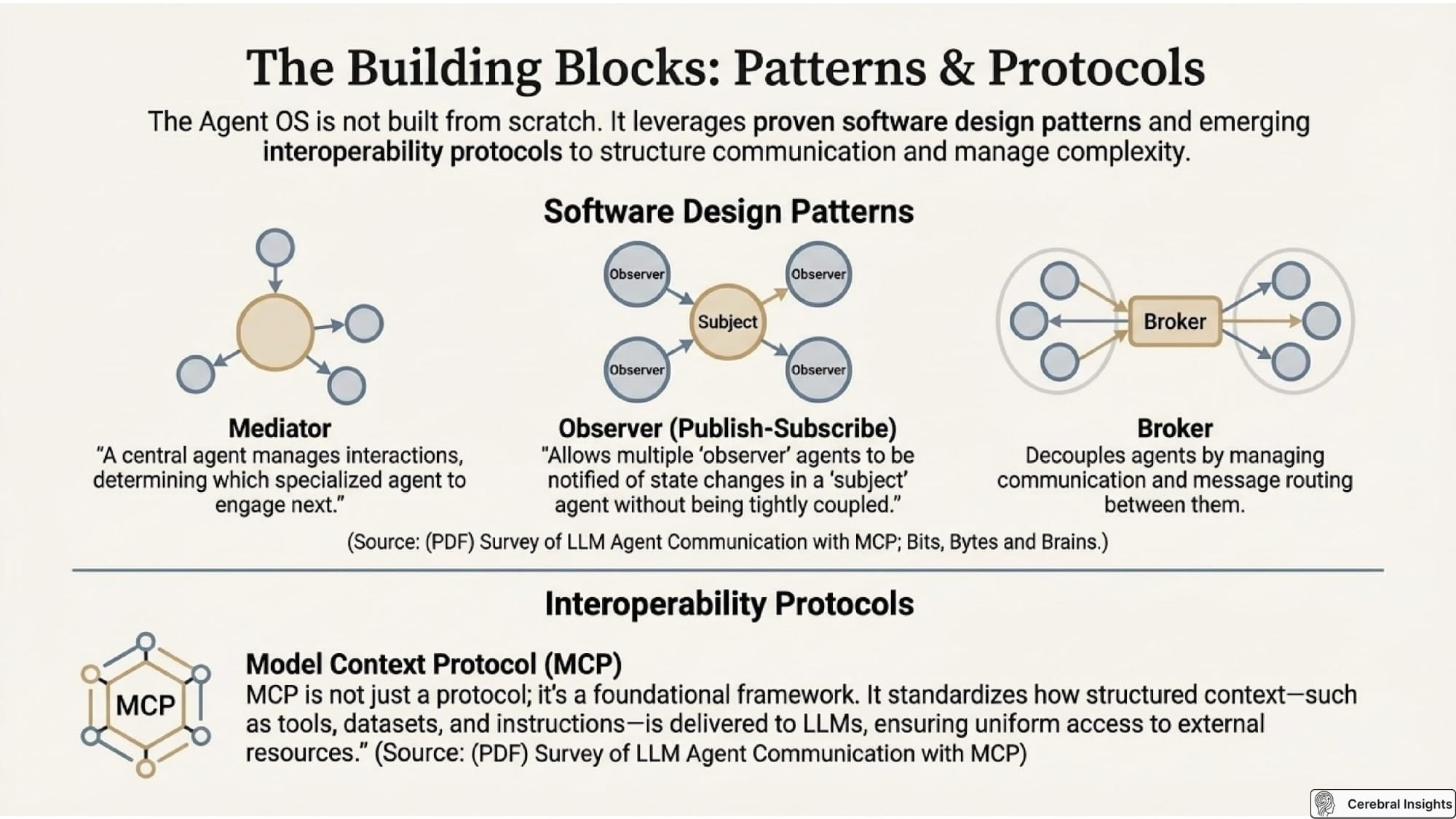

A practical way to implement this is with an "Observer" pattern, which separates the thinking "Doer" (the LLM-based agent) from a more deterministic "Watcher" (heuristic code or another specialized agent). This creates a feedback loop where one agent acts and another validates the outcome, feeding the result back to adjust future actions.

We see this pattern emerging in advanced multi-agent frameworks:

• The S2C framework for control synthesis uses a SolvAgent to generate solutions and a TesterAgent to validate them. Crucially, if the TesterAgent finds a violation, an AdaptAgent updates the problem specification and the loop repeats. This isn't just a two-step process; it's a closed control loop where the TesterAgent acts as the sensor, providing the error signal that directly steers the next action.

• The ControlAgent framework uses a "Python computation agent" to perform complex calculations and evaluations. This agent provides feedback to task-specific LLM agents, which iteratively refine controller parameters to meet system requirements, mimicking the closed-loop process of a human engineer.

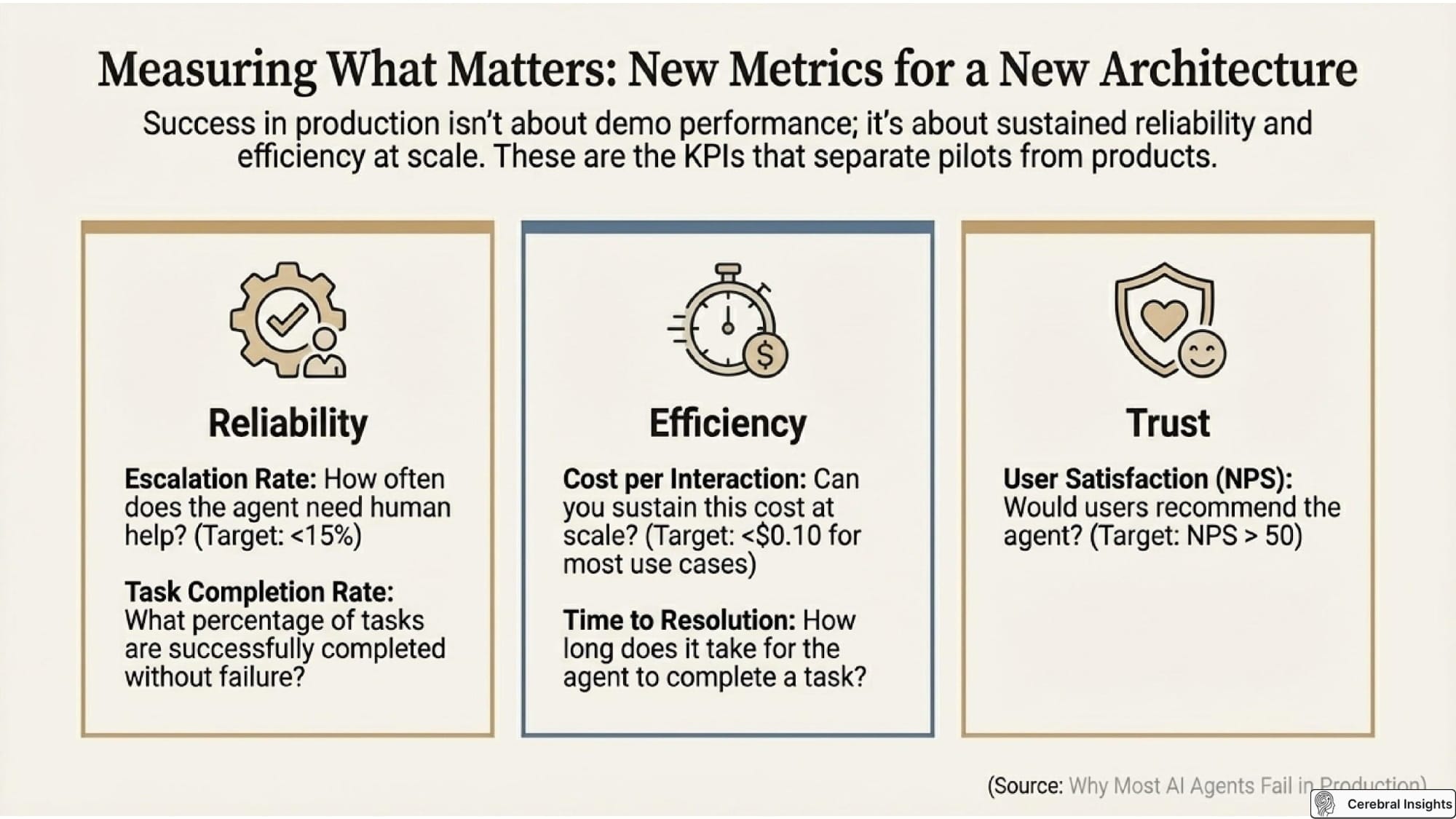

This shift in architecture requires a corresponding shift in how we measure performance. Instead of focusing solely on task "accuracy," we must begin measuring the system's dynamic behavior using metrics from control theory. The key properties for evaluating a control system are its Stability, Accuracy, Settling time, and Overshoot (SASO).

For agentic systems, measuring the "settling time"—how quickly the system converges to a stable state after a disturbance—is particularly critical. As the source material emphasizes, a reliable system must be able to recover and stabilize before the environment or workload changes again, otherwise it will always be reacting to a world that no longer exists.

Conclusion: A New Foundation for Agentic AI

To build truly autonomous and reliable AI systems, we must evolve our thinking. The current focus on prompt engineering and a model's raw intelligence is insufficient for creating systems that can operate dependably in the dynamic, unpredictable real world. The path forward lies in embracing the principles of systems engineering and control theory.

By treating agents not as standalone chatbots but as components within dynamic control systems, we can begin architecting for stability, not just intelligence. This means building closed-loop systems with clear feedback mechanisms, specialized roles, and metrics that value stability and quick recovery as much as task completion.

As we build the next generation of AI, should our primary question be "How can we make agents smarter?" or "How can we make agent systems more stable?"