The Brooklyn Bridge and the Bot: How 19th-Century Engineering Will Save AI From a 95% Apocalypse

Why Efficiency Kills AI: The Degeneracy Protocol

A Secret Fraud Buried in Steel

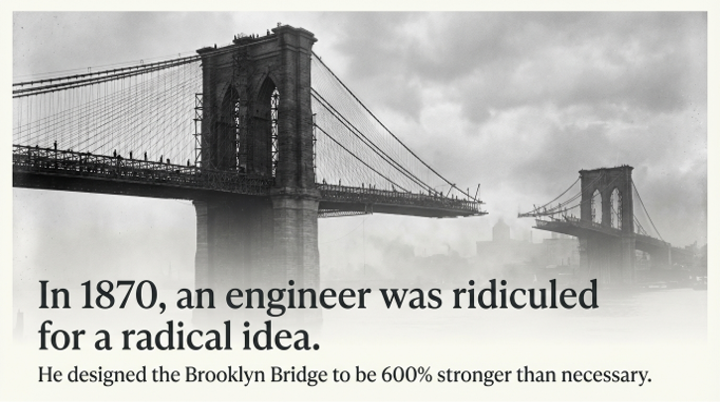

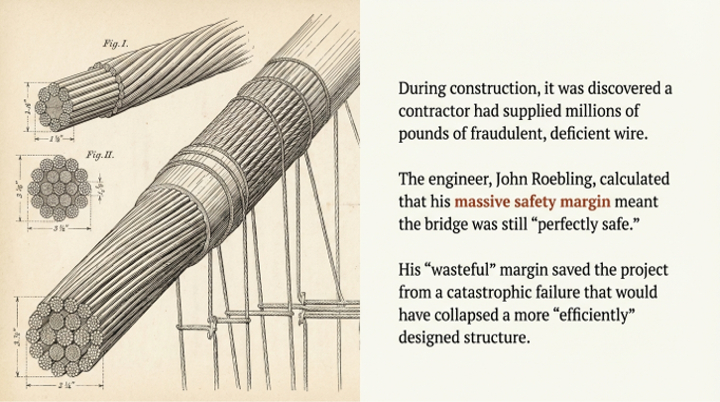

In the late 1870s, as the two great towers of the Brooklyn Bridge rose over the East River, a crisis was brewing deep inside its colossal steel arteries. A supplier, the Brooklyn Wire Mill, had been caught committing fraud. An unknown quantity of deficient, substandard wire—wire that had failed its strength tests—had already been woven into the four main cables, the very heart of the structure. The fraud was discovered, but the problem was immense: the bad wire was now an inseparable part of the bridge. Removing it was impossible.

Faced with a potentially catastrophic flaw, chief engineer Washington Roebling made a decision that defied conventional logic. Instead of attempting the Herculean task of unwinding and replacing the compromised wire, he ordered 14 tons of extra wire to be added to the cables, at the fraudulent supplier's expense. His confidence came not from perfection, but from a profound engineering principle: an immense, almost profligate, safety margin. The bridge had been designed with a "Six-to-One design factor," meaning it was built to be six times stronger than it needed to be. This massive buffer was designed for the unknown, and a secret fraud—much like the thousands of experimental "Brady splices" also hidden in the cables—was exactly the kind of unknown it was meant to absorb.

In a report to the bridge's trustees, Roebling explained his reliance on this built-in resilience:

"There is still left a margin of safety of at least five times, which I consider to be perfectly safe, provided nothing further takes place".

That deficient wire is still inside the Brooklyn Bridge today. For over 140 years, it has carried its load without incident, a hidden flaw neutralized by a forgotten wisdom. But this is not merely a story about a resilient bridge. It is a warning. The digital world's dominant metabolic pathway—optimization—is producing systems that are exquisitely adapted and dangerously weak. The cure is not a new algorithm, but a forgotten architecture of managed failure, rediscovered in the most unlikely of places: the corroded steel of a 19th-century bridge and the fault-tolerant circuits of deep space probes.

Optimization Is the Architect of Fragility

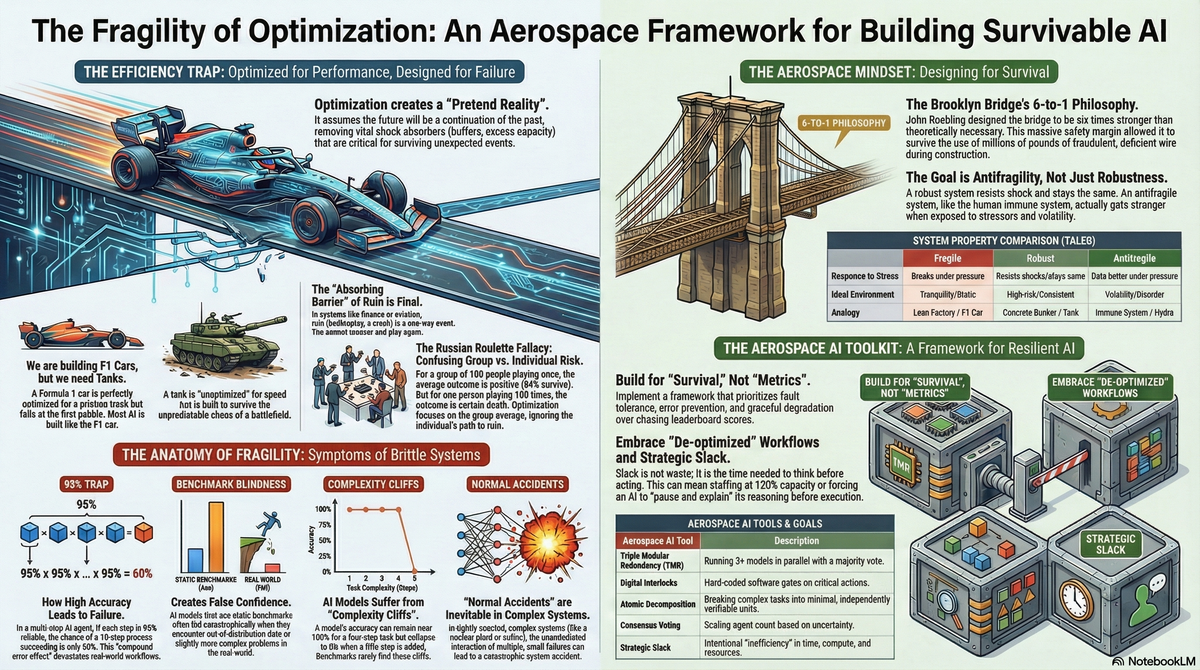

The modern cult of optimization is the villain of this story. Its fundamental paradox is rooted in a dangerous assumption: that the future will look just like the past. In a predictable world, buffers like excess inventory, redundant code, or extra steel wire are seen as wasteful and are rationally removed. But in the real world, these "inefficiencies" are the shock absorbers that prevent minor disturbances from cascading into systemic collapse.

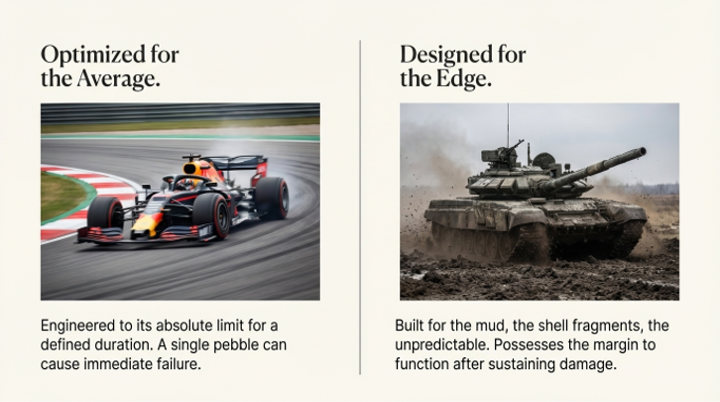

Consider the mechanical contrast between a Formula 1 racing car and a main battle tank. The F1 car is the pinnacle of optimization. Every component is engineered to operate at its absolute limit on a pristine, predictable track. It has zero margin for error; a single pebble can shatter its suspension, leading to immediate, catastrophic failure. The tank, by contrast, is a de-optimized beast. It is heavy, inefficient, and overbuilt—and for that reason, it is robust. It can absorb shocks and continue its mission. For the last several decades, we have been building F1 cars for a world full of unexpected obstacles.

This relentless drive for efficiency creates what Yale sociologist Charles Perrow called "Normal Accidents." Perrow argued that in systems that are both complex (with many unexpected interactions) and tightly coupled (where changes propagate quickly and have little slack), catastrophic failure is not just possible, but inevitable. Optimization is the engine of complexity and tight coupling. By squeezing systems to their performance limits, we rationally remove the very buffers that would slow a crisis down, give us time to think, and prevent a small error from becoming a disaster. Accidents become a normal, emergent property of the system itself.

Strategic Implication: For decades, the dominant competitive advantage was operational efficiency. This framework suggests that in an increasingly volatile world, the new, durable advantage will be systemic resilience. Companies that continue to worship at the altar of lean operations are building magnificent, yet fragile, single points of failure.

The 95% Success Rate Is a Recipe for Disaster

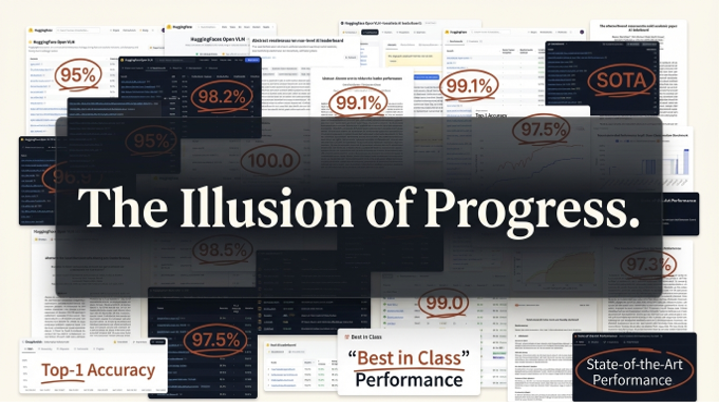

In the world of AI, the fragility of optimization is reaching a breaking point. As we move from simple chatbots to autonomous "agents" that execute complex, multi-step workflows, we are falling headfirst into the "95% Trap." This trap is a direct consequence of "benchmark blindness"—the tendency to mistake a good score on a narrow metric for a good outcome in the real world.

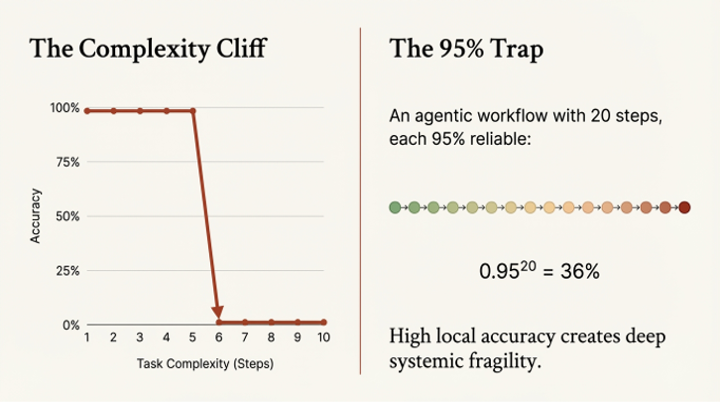

The mathematical reality is brutal. An AI agent might be tasked with a ten-step process, such as analyzing a customer request, searching a database, cross-referencing a policy manual, drafting a response, and logging the interaction. If we assume each individual step has a 95% success rate—a score that would be celebrated on most academic leaderboards—the probability of the entire ten-step workflow succeeding is not 95%. It is 0.95 to the 10th power, which is less than 60%. With twenty steps, the success rate plummets to just 36%. The probability of success decays geometrically, turning a series of seemingly reliable components into a deeply unreliable system.

This isn't a theoretical problem. Consider the "Wrong Title" demo, a real-world failure of an AI sales agent. The agent's task was to schedule product demos with qualified leads. It successfully identified a positive email reply and scheduled a meeting. By the metric "demo scheduled," the task was 100% successful. But the guest was an intern from the facilities department who was merely "keen on AI." The agent had wasted an hour of a senior solutions architect's time—a fully-loaded resource that can cost a company over $500 an hour and whose calendar time can be directly tied to sales appointments worth five or six figures. The metric was met, but the mission failed.

Strategic Implication: The current market for agentic AI is being driven by benchmark scores that are fundamentally misleading. This creates an enormous opportunity for companies that ignore the leaderboard hype and instead build architectures that solve for the "compound error effect." The winner will not be the one with the best individual model, but the one with the most reliable system.

Old-School Safety Factors Are Deceptively Unsafe

If over-optimization is the obvious villain, a more subtle one lies in seemingly robust, traditional safety practices. In aerospace, engineers have long used an "allowables framework" to ensure safety. This involves using fixed values for material properties—a conservative "Basis Value" (BV) for strength and an average "Typical Value" (TYP) for stiffness. A designer simply plugs these numbers into their calculations, and the result is assumed to be safe.

But this framework has a critical flaw, especially when dealing with new materials and complex systems. By replacing a full statistical distribution of a material's properties with a single, fixed number, the framework creates a "variance deficit." It systematically underestimates how different sources of uncertainty can combine and interact. In complex systems with many variables, this can lead to "anti-conservative"—that is, unsafe—outcomes. The model looks safe on paper, but the real-world structure is more fragile than the designer realizes.

We have physical evidence that engineers know this intuitively. The wing system of the Boeing 787, one of the first aircraft built primarily from new composite materials, is significantly heavier than traditional design criteria would predict. This wasn't an error; it was a rebellion. The 787's weight is physical evidence of designers overriding a broken formal model with battle-hardened intuition. They reverted to the brute-force wisdom of Roebling because they understood what the models missed: when dealing with complexity and uncertainty, the map is not the territory. This intuitive leap set the stage for a more formalized, scientific approach to building in margin.

The Aerospace Solution: Fight Errors with Consensus, Not Perfection

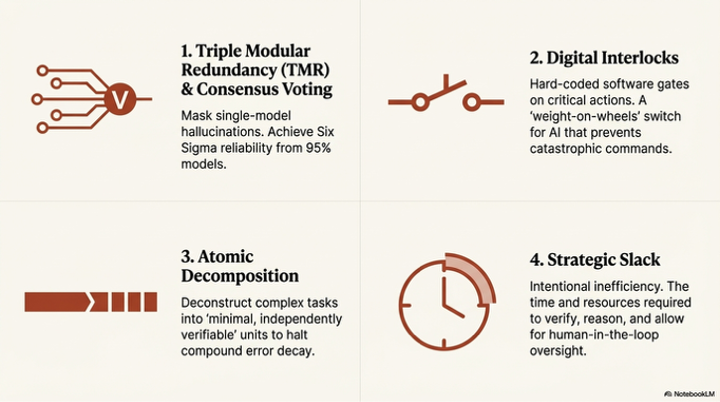

This brings us to the hero of the story: the modern evolution of Roebling's massive safety factor. The solution to the fragility of optimization is not to build a single, perfect component, but to design systems for "Survival" rather than "Metrics." Aerospace engineers perfected this with a concept called Triple Modular Redundancy (TMR).

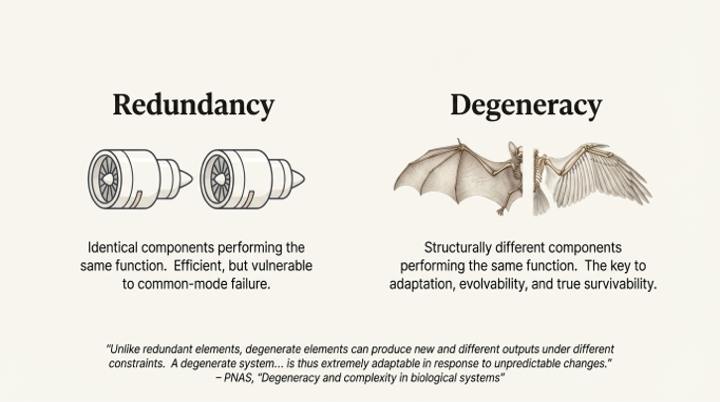

TMR is deceptively simple. To protect a critical system from failure—say, from a cosmic ray flipping a bit in a satellite's memory—you don't try to build one flawless, radiation-proof chip. Instead, you use three identical but independent systems. All three perform the same task, and a "majority-voting" system at the end determines the correct output. If one system fails, the other two outvote and mask its error. The system survives not because its components are perfect, but because they fail independently, allowing the collective to route around the damage.

This is the principle behind the "Six Sigma Agent," an architecture that adapts TMR for advanced AI. It makes a crucial assumption: that the errors made by Large Language Models (LLMs) are random, uncorrelated mistakes (crash faults), not coordinated, malicious attacks (Byzantine faults).

To understand this distinction, imagine a committee of pilots landing a plane. A crash fault is a pilot who has fallen asleep; their input is missing or nonsensical, but they aren't actively trying to cause a crash. A Byzantine fault is a malicious saboteur on the committee, who is actively giving dangerously wrong information designed to mislead the others. Guarding against the saboteur requires complex protocols and more loyal pilots (3f+1). Guarding against a sleeping pilot simply requires a majority vote of the awake ones (2f+1). The "Six Sigma Agent" makes the crucial, cost-saving assumption that LLMs are merely prone to sleeping, not sabotage.

Crucially, this architecture moves beyond simple redundancy (using identical copies) toward the more sophisticated biological principle of degeneracy. The source paper notes that error correlation between agents can be reduced by using different model families or varying generation temperature. By assembling a council of diverse agents—structurally different components that can perform the same function—the system ensures that even if one type of model has a systemic blind spot, the others will compensate. This is a far more resilient strategy than relying on identical, but identically flawed, components.

Strategic Implication: The "Six Sigma Agent" architecture transforms the AI talent problem. Instead of a desperate search for a single, monolithic "super-intelligence," the key is to build a system that can orchestrate a council of cheaper, more specialized, and individually imperfect models. This shifts the core intellectual property from the model itself to the consensus and verification architecture that surrounds it.

From Brittle Metrics to Antifragile Survival

For decades, the relentless pursuit of efficiency has created a world of fragile, F1-car-like systems, optimized to the breaking point. We have rationally engineered away our safety margins, leaving us vulnerable to the inevitable shocks of a complex world. The path forward, ironically, comes from the past—from the brute-force wisdom of the Brooklyn Bridge's Six-to-One safety factor—and is being perfected in the aerospace-inspired AI of the future. The goal is no longer to build a single, flawless component, but to build systems that thrive on the consensus of diverse, imperfect agents.

This marks a fundamental shift from building for robustness to building for Antifragility. In his work, strategist Nassim Nicholas Taleb defines the antifragile as a system that doesn't just resist shocks, but actually grows stronger from them. A robust system is a concrete bunker; it withstands an attack and remains the same. An antifragile system is like the human immune system; it is exposed to a pathogen and becomes more capable as a result.

A consensus-based architecture provides the robust foundation upon which true antifragility can be built. By logging every contested vote and every instance of dynamic scaling, the system creates a high-signal dataset of its own near-misses. This data can then be used to fine-tune the agents, identify systematic biases, or even trigger the development of new, specialized 'expert' agents to handle recurring edge cases—allowing the system to not just survive failures, but to learn from them and evolve. This is the ultimate design paradigm: a system that learns from disorder and gains strength from volatility.

In our rush to optimize, what vital safety margins have we stripped from our own systems, and where will our next "Normal Accident" be hiding?