The Invisible Tax: Why Physics, Not Parameters, Dictates the Future of AI

The AI Margin Trap: Training Hurts Once, Inference Bleeds Forever

The Illusion of Free Intelligence

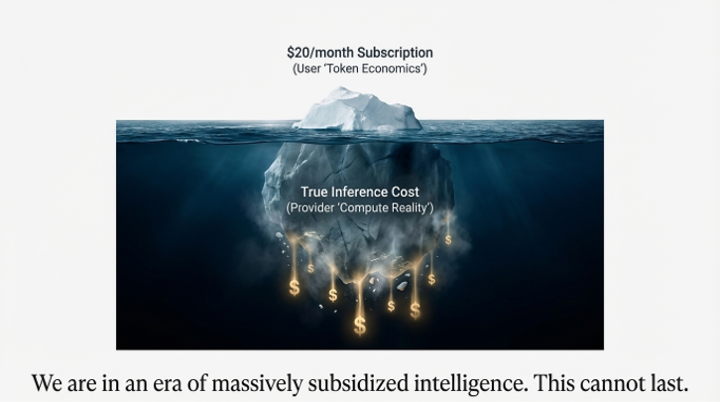

For the user, artificial intelligence feels like magic on a fixed budget. A flat $20 monthly subscription unlocks a frontier model, a tireless digital collaborator ready to code, write, and reason on command. The experience is simple, affordable, almost weightless.

For the provider, it is a brutal economic cage match against physics. While the enormous cost of training a model is a one-time capital expenditure, every single user query—every sentence completion, every line of code generated—triggers a real, recurring operational cost. This is the relentless drumbeat of inference. Unlike traditional software-as-a-service (SaaS) where an extra user costs fractions of a penny, for an AI company, inference compute is a direct, variable Cost of Goods Sold (COGS) that explodes with usage. As one analysis notes, an AI company’s “COGS rides someone else’s price card”—their margins are lashed directly to their model provider’s API pricing.

The current model is unsustainable. As startups race for market share, they are subsidizing this invisible tax. Bessemer Venture Partners observes that in this land-grab, AI startup margins are often "stretched close to zero or even negative." This reality cannot last.

So, what happens when the subsidy ends?

The Villain Isn't Intelligence, It's Bandwidth

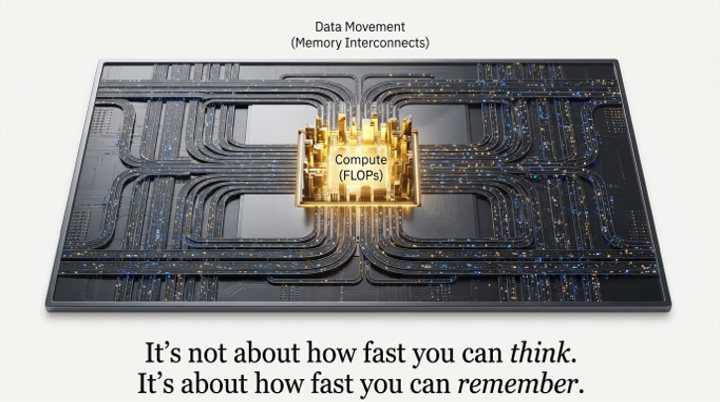

The common narrative of the AI race has a clear villain: scale. The primary constraint, we are told, is the number of parameters in a model or the raw computational power, measured in FLOPS (floating-point operations per second), needed to train it. Bigger, it seems, is always better.

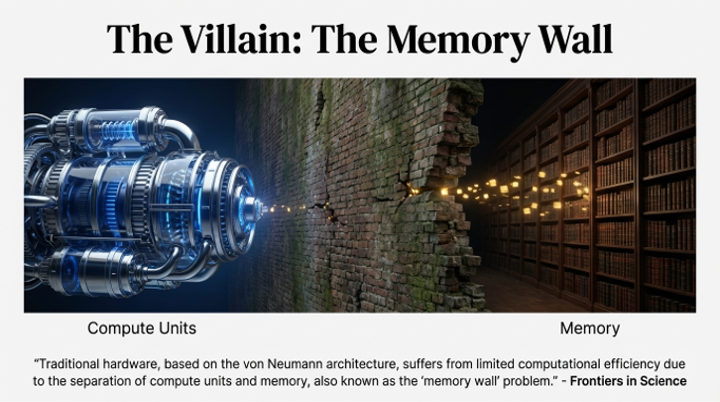

But this fixation on scale is the central illusion of the AI arms race. The true antagonist isn't the size of the model's brain; it's the physics of its nervous system. The real bottleneck, the fundamental governor on AI’s future, is a concept from computer architecture known as the Memory Wall.

For decades, hardware compute capabilities have advanced at a blistering pace, far outstripping the speed at which data can be moved from memory to the processor. We’ve built race cars with thimbles for fuel lines. The problem is not how fast a GPU can think, but how fast it can remember. As researchers at UC Berkeley note, the decoder models that power today's generative AI have "orders of magnitude smaller arithmetic intensity," meaning they are structurally incapable of keeping the hardware’s powerful compute units fed with data. The result is a math monster being starved, a state-of-the-art processor waiting idly for the next piece of information to arrive.

Three Pillars of the New AI Reality

To understand the future, we must grasp the constraints of the present. The new AI reality is built on three pillars: a broken economic model, a hard physical limit, and the new architecture required for survival.

A. The Economic Trap of Unsustainable Scale

The financial logic of AI is fundamentally different from the cloud software that preceded it. Traditional SaaS businesses are prized for gross margins comfortably in the 80-90% range. In contrast, the new benchmark for fast-growing AI “Shooting Stars,” according to a Bessemer Venture Partners report, is around 60%.

This margin compression is a direct result of inference costs. This isn't a theoretical squeeze; it’s the reality that led one fintech's chatbot to burn "$400 per day" for a single client, turning a prized customer into a financial liability. Because every user action can trigger a call to a third-party model, costs scale directly with engagement, creating a precarious dependency where profitability is dictated by a provider’s API prices. Under this model, simply scaling usage doesn’t automatically improve unit economics as it does in classic SaaS; in fact, it can worsen them if pricing isn’t perfectly aligned with cost. This is why pure scaling, as a strategy, eventually collides with the brutal mathematics of diminishing returns. Research on LLM scaling laws reveals punishingly low exponents (α ≈ 0.1 or less), meaning each subsequent order-of-magnitude increase in compute, data, or parameters yields only a tiny, fractional improvement in model quality. The economic path to better models is not just steep; it's nearly vertical.

B. The Physics of the Bottleneck

The economic pain is a symptom of a deeper, physical constraint. To operate an AI service at scale is to fight a constant battle against the Memory Wall.

This is the fundamental limit on performance imposed by the time and energy it takes to move data between a processor and its memory. It is the inescapable tax of physics on computation. In AI, this tax is paid every time the model processes a new piece of information.

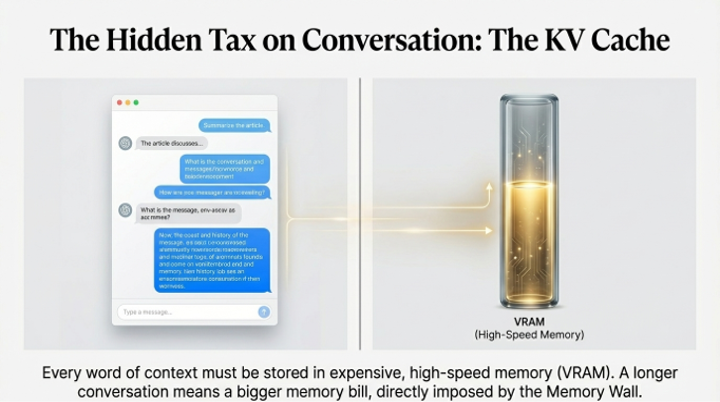

The most acute manifestation of this problem lies in the KV Cache. Think of the KV Cache as the model's short-term memory for a single conversation. To generate a coherent response, the model must hold the "key" and "value" tensors for every previous token in the conversation's context. As the conversation gets longer, this cache grows linearly, consuming vast amounts of a GPU’s precious and expensive high-bandwidth memory (VRAM). This memory pressure directly limits batch size—the number of user requests that can be processed simultaneously—which is the primary lever for cost efficiency.

This creates the core operational dilemma for any AI service: the trade-off between Latency and Throughput. To make inference cheaper per user, providers want to batch as many requests together as possible to maximize GPU utilization (increasing throughput). However, grouping requests means some users have to wait longer for others, which increases the time-to-first-token (increasing latency). Every AI provider must navigate this treacherous balance between a responsive user experience and a viable business model.

C. The Architecture of Survival

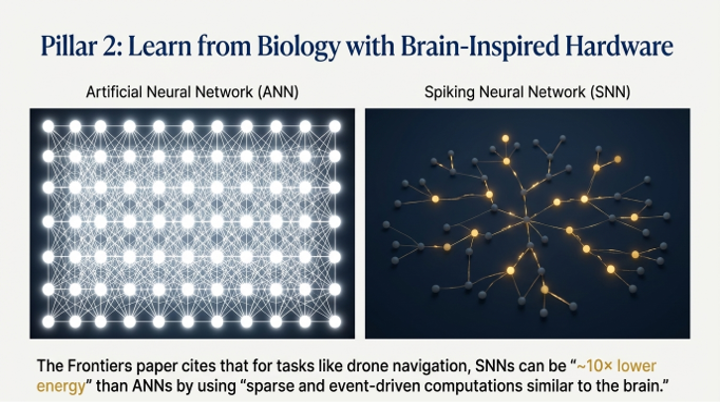

The response to these economic and physical walls is not to build bigger models, but to build smarter systems. The architecture of survival is one of ruthless optimization and strategic precision.

The first strategy is Right-Sized Model Architecture. An emerging economic necessity is to stop using a sledgehammer to crack a nut. As Umbrex notes, routing a user's request to the "smallest acceptable model" is a critical lever that can "cut cost dramatically." This means a sophisticated routing layer that analyzes a prompt and sends it to the cheapest model that can meet the quality bar, reserving the expensive frontier models for only the most complex tasks. The future is not one model to rule them all, but a diverse fleet of large, small, specialized, and on-device models.

The second strategy is to Cheat the Physics with a new class of optimization techniques designed to mitigate the memory bottleneck. These are not incremental tweaks; they are fundamental changes to how models operate:

• Speculative Decoding: This technique uses a small, fast "draft" model to generate a sequence of likely future tokens. The large, powerful model then only needs to perform a single verification step on the entire sequence, radically reducing the number of sequential, memory-intensive steps it must perform.

• Attention Optimization: Techniques like Multi-Query Attention fundamentally alter the structure of the model's "head" to share key-value projections across attention computations. This drastically reduces the size of the KV Cache, saving memory and bandwidth with each token generated.

• Quantization: This is the art of using lower-precision numbers to represent the model's weights. By converting from 16-bit floating-point numbers to 8-bit or even 4-bit integers (INT8/INT4), companies can significantly reduce the model's memory footprint and bandwidth requirements, accelerating throughput on compatible hardware.

These strategies redefine the meaning of a strategic "moat" in AI. The durable advantage is not the model itself—"not just weights"—but the entire, hyper-efficient system. The moat is the routing logic, the optimized inference stack, and the mastery of "context and memory." An organization that masters these physics possesses an execution moat of operational excellence—a fortress far harder to assail than one built merely on proprietary model weights.

The Prediction: The Great Fragmentation

The first era of modern AI was defined by a monolithic race to scale. The next five years will be defined by its opposite: The Great Fragmentation.

This is not a strategic choice, but a physical and economic inevitability. The invisible tax of memory bandwidth will force a retreat from monolithic design. The obsession with building a single, ever-larger model as the sole source of intelligence is an economic and physical dead end. The future belongs to a diverse, fragmented ecosystem of architectures. There will be massive frontier models for complex reasoning, but they will be complemented by fleets of smaller, specialized models, fine-tuned for specific domains and running on-device or at the edge.

The winning companies will not be those with the biggest models, but those with the most efficient inference stacks. They will become masters of compute economics, wielding a portfolio of models like a scalpel, not a sledgehammer. They will build systems that understand not just language, but latency, cost, and the physics of memory.

In the next era of AI, victory won't be determined by the size of a model's brain, but by the efficiency of its nervous system.